Suzanne Spellen's Tales of Brooklyn History and Architecture in 2023

Historian Suzanne Spellen returned to Brownstoner for a regular monthly column this summer, bringing in-depth stories of Brooklyn’s history and architecture every month.

By an unknown architect, the understated red brick station at 409 State Street in Boerum Hill opened in 1889 and houses Engine 226. Photo by Susan De Vries

Historian, preservationist, and longtime Brownstoner columnist Suzanne Spellen returned to Brownstoner for a regular monthly column this summer, bringing in-depth stories of Brooklyn’s history and architecture every month. If you missed her 2023 columns or her features in the Brownstoner print magazine, we’ve rounded them up for some winter reading below.

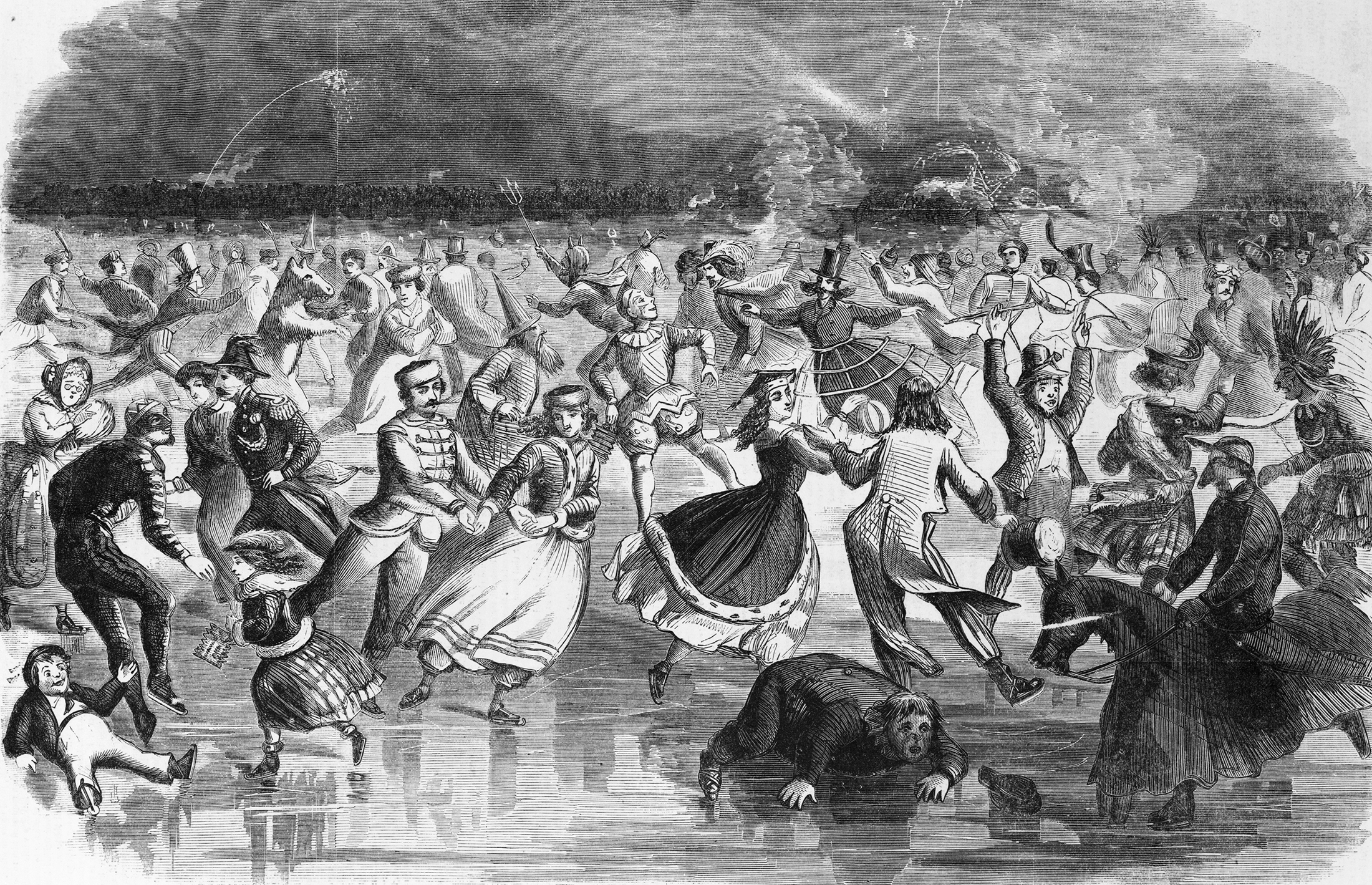

A Winter Wonderland: Ice Skating and Frosty Frolics in 19th Century Brooklyn

The post-Civil War years were a period of great change in American society. For the first time, an ever-growing middle class emerged, one that had more leisure time than ever before and money to spend. Brooklyn was a manufacturing city back then. Its industrial hubs along the East River and further inland were supported by factories churning out all kinds of goods like furniture, glass, and porcelain, as well as foodstuffs, linens and lace, timepieces, and home furnishings. While many jobs were low-paying factory gigs, a white-collar class of workers emerged from this new economy — bookkeepers, brokers, middle management, professionals, teachers and much more — and they made the most of it.

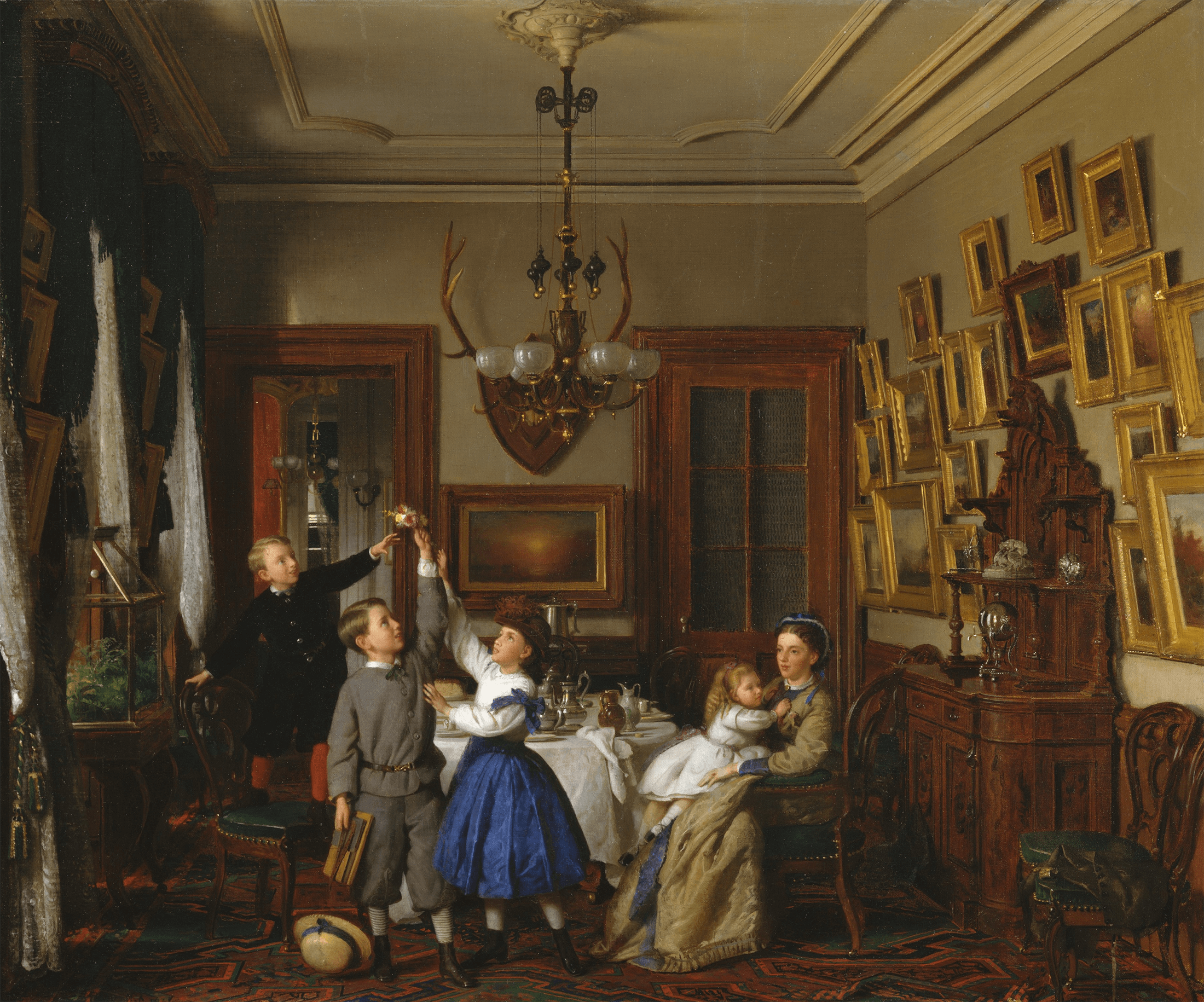

A Quick History of the Dining Room and Its Decoration in Brooklyn and Beyond

Thanksgiving was meant to be a day set aside for the giving of thanks for the harvest, the bounty of the earth, and the gifts of nature and prosperity bestowed on us throughout the year. In celebration, we gather for a feast that brings together extended family, friends, and strangers to our tables. There are only a handful of countries that celebrate a day called Thanksgiving — the U.S. and Canada chief among them — but many other countries also have traditional harvest feast days and celebrations by other names.

‘I Only Do Big Things’: Woman, Architect, and Brooklynite Fay Kellogg

There always must be the “firsts,” those who defy convention and setbacks, and succeed in opening new worlds for women in careers that were once closed to them. In the late 19th century, as Brooklyn was growing block by block, there were a few women who became row house developers and were the architects of record in many cases. They usually had to change their names, or go by their initials, or be fronted by their husbands. Some of their stories are here.

One woman set out to be an architect in her own right, receiving the same or better education as her male counterparts. She worked in major architecture firms and eventually established her own practice, not hiding her gender or abilities. She became the country’s first well-known female architect. She proved that a woman could design any kind of building and walk up and down a high-rise construction site with the best of them. She was Brooklyn’s own Fay Kellog.

Rene Chambellan, Art Deco Architecture’s Master Sculptor, in Brooklyn and Beyond

The Art Deco period of 20th century art and architecture was an inventive Jazz Age take on themes first introduced centuries before. It was the final phase of the Age of Ornament, which became such a staple of 19th century Western architecture. An American artist with a very French name was the master of architectural sculpture during this creative period, commissioned to sculpt the ornamentation that decorates some of the nation’s most well known and significant buildings, from Michigan to Brooklyn. You may not know his name, but you’ve seen his work. He was Rene Paul Chambellan.

Civic Pride: From Romanesque Revival to Neo-Brutalist, Brooklyn’s Firehouses Impress

Any municipality may have beautiful homes and impressive cultural, religious, and commercial structures, but what really makes a city great in terms of outward appearance is the quality and quantity of its civic buildings. The architecture and appearance of schools, courthouses, police stations, firehouses, and infrastructure buildings were important in the late 19th century. They were something everyone could point to and be proud of, an outward representation of the responsibility city government had to take care of its citizens.

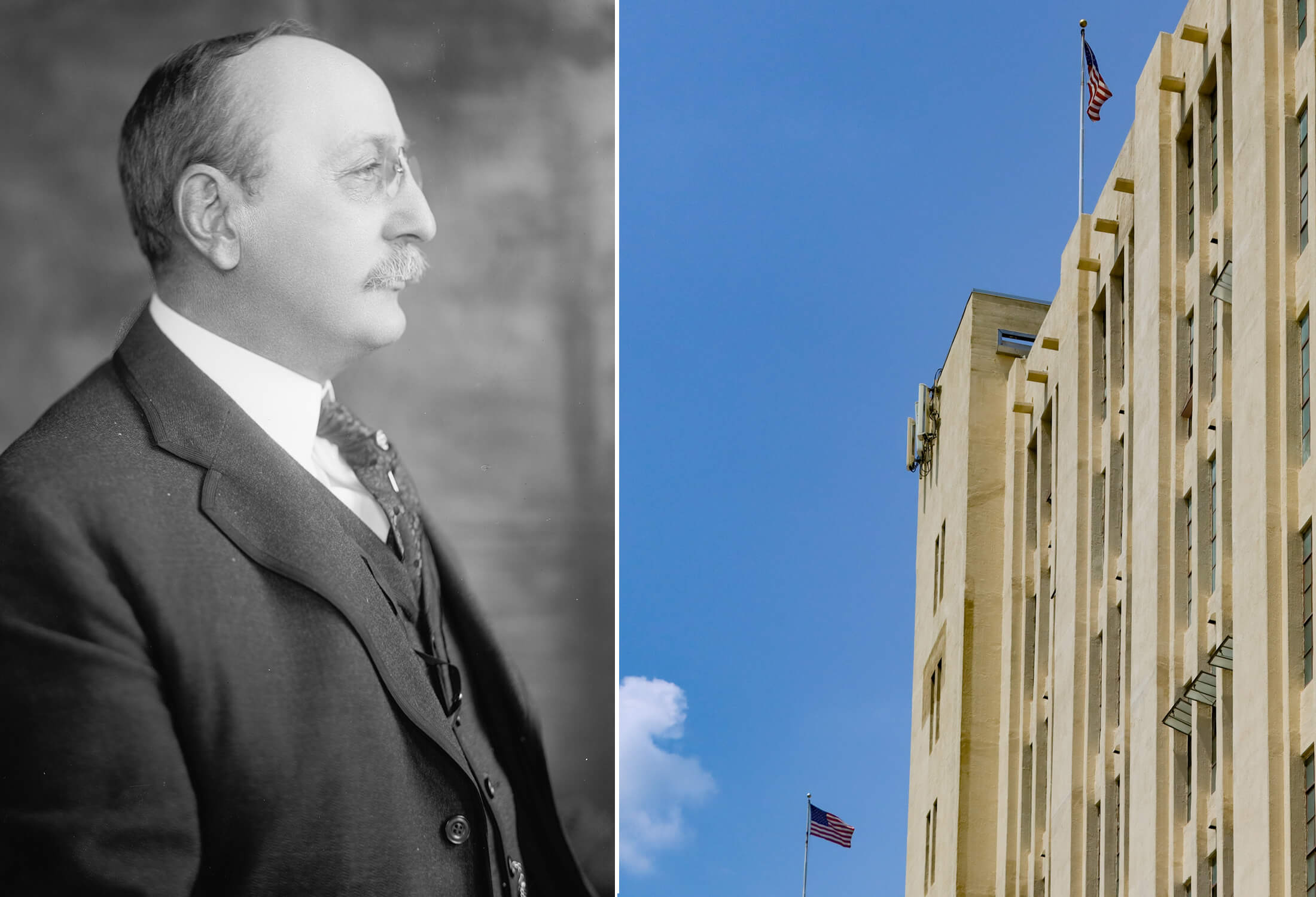

Architect Cass Gilbert Designed Innovative and Inspiring Public and Commercial Buildings

There were two very talented architects named “Gilbert” working in Brooklyn and New York City at the turn of the 20th century and beyond. Many people confuse them, but Frank W. Woolworth hired both. Charles Pierrepont Henry (C.P.H.) Gilbert designed gorgeous brownstone, brick, and terra-cotta mansions in Brooklyn and gleaming limestone castles for Manhattan’s high society, including one for Woolworth. Cass Gilbert was a master of the new “skyscrapers,” a Classicist who created some of the nation’s most well-known buildings and a futurist who used the newest building tools and materials with great skill and beauty. He designed his most famous skyscraper for the same Frank Woolworth and this is his story.

The Many Lives of Downtown Brooklyn’s Offerman Building

By the beginning of the 1890s, Fulton Street between City Hall and Flatbush Avenue was fast evolving as one of the largest and most prosperous retail shopping districts in the nation. Large department stores such as Weschler & Abraham, Frederick Loeser and A.D. Matthews dominated, all housed in new and ever-larger multi-storied buildings along the length of the blocks.

Journey by Faith: The Story of Brooklyn’s Black Churches

By the early 19th century, the town of Brooklyn lay nestled on the shore of the East River in what is today Dumbo. Not yet a city, it was still a collection of wood-framed buildings, with businesses and industry scattered among the taverns, churches, and homes. These early Brooklynites were from all walks of life and social classes and included a population of enslaved African Americans, as well as a community of free Black people. The latter included men and women who were employed as domestics and general laborers, as well as those who had their own businesses as rope makers, shoemakers, barbers, house painters, laundresses, and more.

Related Stories

- A Library for All: The Story of Brooklyn’s Central Library, Decades in the Making

- From Practical to Ornamental: The History of Dressing Windows

- The Hiram S. Thomas Story: Brownstones, Potato Chips, Black Excellence in 19th Century Brooklyn

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment