A Walk Through Shirley Chisholm's Brooklyn

From Central Brooklyn, Shirley Chisholm was the first African American woman elected to Congress in the history of the United States and spent her life pursuing justice and social equality for all people, especially those in poverty.

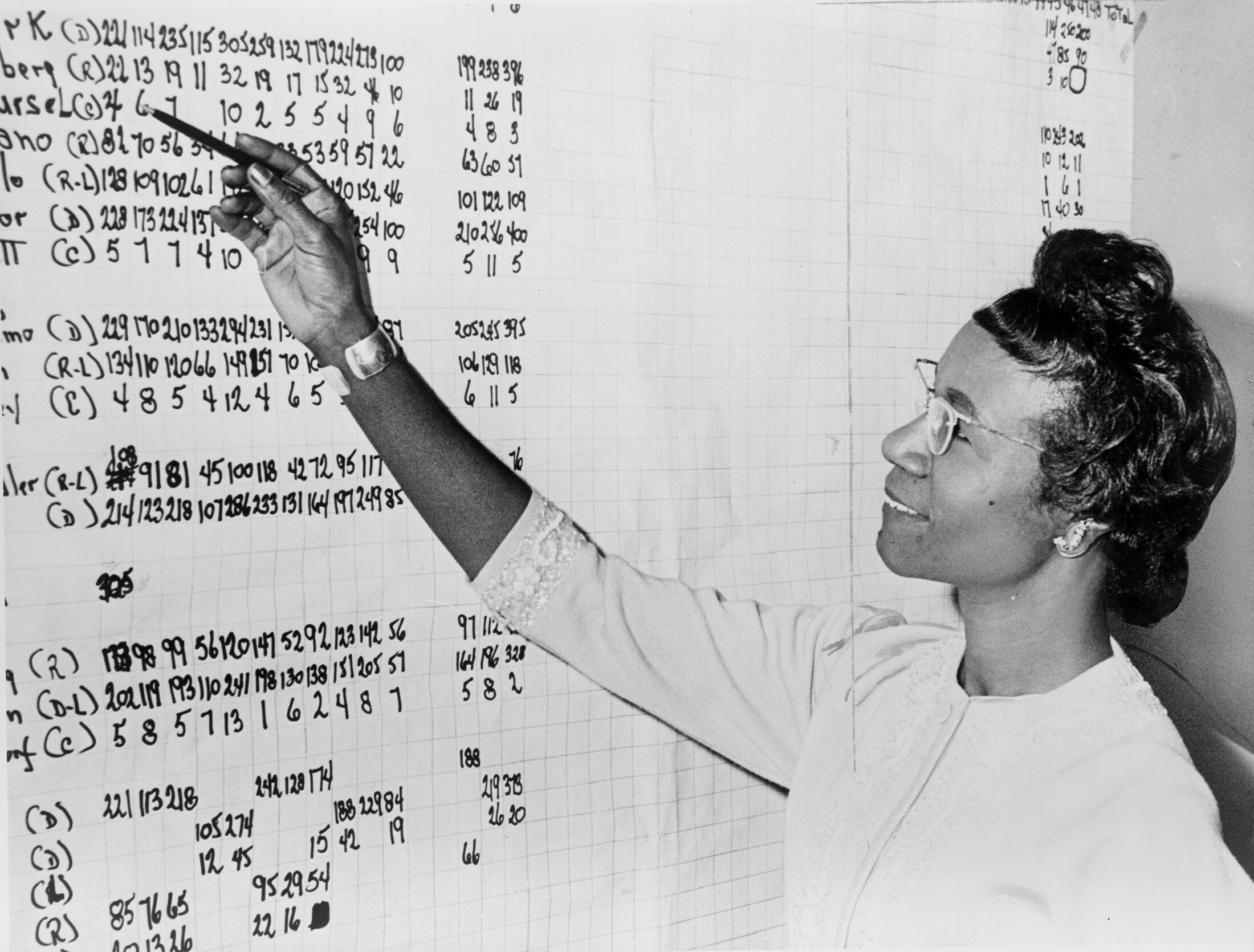

Portrait of Shirley Chisholm by Thomas J. O’Halloran via Library of Congress

Editor’s note: This story is an update of one that ran in 2015. Read the original here.

When I was growing up, I knew who Shirley Chisholm was. I come from that generation of African American children whose parents made sure we knew who all of the “firsts” were. Kids growing up today take the many achievements of African Americans for granted, and that’s a great thing, because we should be able to achieve whatever we want without notice or fuss.

We shouldn’t have to be able to make a list of the number of Black nuclear scientists, cancer researchers, neurosurgeons, fashion designers, Oscar winners, hockey players or even Republicans; we should be able to be well represented in all facets of American life.

But when I was in my formative years, during the 1960s, we were just getting to the point where there were a lot of “firsts.”

The Civil Rights Movement, which happened right before my eyes on our black-and-white television, was both sobering and inspiring. We grew up checking the pages of Ebony magazine, the Black version of Life, which always had articles about those Black folks who had arrived — pioneers in all walks of life, “firsts” or sometimes only “seconds” or “thirds” in every field we had managed to conquer.

Shirley Chisholm was one of those proud pioneers, and as a female, she was of special interest to my mother, and thus, to me.

But it wasn’t until I actually moved to Brooklyn that I realized what that all meant. It’s easy to be somewhere else reading about great people of any nationality, time or location and be inspired, but when you live where they lived, walk past the buildings they were educated, worked or lived in, and see the world they saw, you get a special affinity for what it was like to shape that landscape and those people into history.

While I lived in Brooklyn, I lived in Shirley Chisholm’s stomping ground, and so in honor of her achievements, I’d like to propose a Shirley Chisholm Walking Tour.

In 1968, Shirley Chisholm was the first African American woman elected to Congress in the history of the United States. She was also the first major-party Black candidate for president of the United States, and the first woman to run for the Democratic nomination for president, in 1972. That’s a nice set of “firsts.”

She was born in Brooklyn on November 20, 1924. Her mother, Ruby Seale, was from Christ Church, Barbados, and her father, Charles Christopher St. Hill, was from British Guiana, now Guyana. Both had come to America at a time when many Caribbean people were emigrating to the United States, Great Britain and Canada from English speaking Caribbean colonies.

Coincidentally, my own father was also born in British Guiana and immigrated with his parents to the United States in 1926, when he was six months old. He was also born in November, and spent his earliest years in Brooklyn. They would have been contemporaries, had they known each other. Perhaps that is also part of the reason why I find her story so interesting and compelling.

Shirley Anita St. Hill was the oldest of four daughters, born to a burlap factory worker and a seamstress. When she was 3, her parents sent her and her two sisters to live with her grandmother in Barbados. When she was old enough, she attended the Vauxhall Primary School, the local school. British educational standards, even in the colonies, were strict and the education was exemplary. Shirley and her sisters came back to Brooklyn seven years later, in 1934, miles ahead of their Brooklyn school mates.

That British education gave her a superior head start, as well as a bit of British pronunciation that never left her, and she was soon a top student. She easily matriculated into the prestigious Girls High School on Nostrand Avenue in Bedford Stuyvesant, and it is here that our Shirley Chisholm walking tour begins.

1. Girls High School: Girls High School, at 457 Nostrand Avenue, between Macon and Halsey Streets, was built in 1885 as Brooklyn’s first high school.

It was designed in the High Victorian Gothic style by James Naughton, the Superintendent of Buildings for the Brooklyn School System, and the architect of all of the schools built in Brooklyn during his tenure between 1878 and 1896, when he died. Girls High School was built as an experiment in public education, and was the first high school in New York City.

Up until that point, a free public-school education ended after grammar school. By the time the building was completed, there were so many eligible students that the Board of Education decided to make this building the girls’ school, and set to work designing a separate high school for boys, which opened several years later.

Both schools are in Bedford, highlighting that neighborhood’s prestige and importance. By 1885, Bedford was one of the fastest growing and most desirable neighborhoods in Brooklyn, and having the school here was a major coup.

The school only accepted the best female students. Even 50 years later, by the time Shirley Chisholm was eligible, in 1939, the school was still quite elite. The schools had been integrated for many years at that point, but Shirley would still have been a minority student in a high school in a neighborhood that was rapidly becoming more and more African American.

Shirley excelled at Girls. She was vice president of the Junior Arista Honor Society, a rarity, as most Black girls were not steered into honors programs. She also graduated with a medal of excellence in French.

She won scholarships to both Vassar and Oberlin Colleges, but could not go, because her parents couldn’t afford the room and board. She opted to go to Brooklyn College instead.

Naturally, she excelled there, as well. She had decided to become a teacher, but majored in sociology and minored in Spanish, and was fluent in the language. She was a champion on her debating team, and a member of the Delta Sigma Theta Sorority.

When a social club refused to accept Blacks, she founded an alternative club, her first foray into getting what she wanted in spite of what other people thought. She graduated cum laude from Brooklyn College in 1946.

Unfortunately, Brooklyn College is a little far to walk for this tour. But by 1945, her equally hardworking parents had saved up enough money to buy a house, the goal for every Caribbean immigrant of their day. It was a row house on Prospect Place, between Kingston and Albany avenues, in what was still considered Bedford Stuyvesant at that time. Today, it’s part of Crown Heights North.

2. Prospect Place “Superblock”: This block is one of two “Superblocks,” so designated in the 1960s as part of a pilot program by the Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation. But back in 1945, it was just another row-house block.

The Albany Avenue side of the block faced the large Catholic orphanage complex, the St. John’s Home for Boys, which had been there since the late 1800s. The Kingston Avenue end of the block faces Brower Park, creating a lovely rather isolated block filled with a mixture of two-story limestone row houses, a couple of small flats buildings, a set of double duplex houses and some earlier wood framed houses and brick row houses.

The limestone row houses were developed in 1901 and designed by Axel Hedman, the master of the Renaissance Revival row house, and the architect of hundreds of these houses in Crown Heights North and South, Stuyvesant Heights, Prospect Heights, Park Slope and Flatbush. The houses had a duplex apartment on the bottom two floors and a separate apartment on the top floor.

During the time the St. Hill family bought their home at 1094 Prospect Place, many of these houses were further subdivided into rooming houses for extra income. Families often sacrificed personal comfort and space in order to own their homes. Redlining in this neighborhood made home ownership even more difficult, but thousands made it work by working several jobs, and renting out as much as they could.

Shirley St. Hill lived on this block for the year she was still attending Brooklyn College. One of her sisters moved from home and lived across the street, renting a room in 1081 Prospect Place. The block has always had a lot of pride, and was home to African American strivers of many kinds.

One of the famous Tuskegee Airmen settled with his family on this block after World War II. They had a longstanding block association, and the block was like many Bed Stuy blocks — clean and safe.

This quiet block was in the enormous neighborhood known as Bedford Stuyvesant. By the beginning of the 1960s, the entire neighborhood, the size of a small city, had been written off as the “Worst Ghetto in America,” by the press, social scientists and city leaders.

Many of the blocks were filled with abandoned and burned out buildings. Urban renewal had mowed down block after block of low density row houses to build high rise housing projects, and the factory jobs which had fueled the local economy had all closed up and disappeared.

The city had cut back on sanitation, repairs and services, and crime and misery had rendered some parts of Bed Stuy about as miserable as an American urban ghetto could get.

Of course, not every block was miserable. Local leaders knew that much of Bedford Stuyvesant was still filled with blocks like Prospect Place. When the Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation was established by local community leaders and senators Robert F. Kennedy and Jacob Javits, in 1966, one of their goals was to make sure blocks like Prospect Place were replicated throughout the area.

Kennedy, Javits and local leaders toured the vastness of Bedford Stuyvesant and chose this block and the adjoining St. Marks Avenue, right behind it, as the two blocks that would be a pilot program for future urban planning. They were called “Superblocks.”

Kennedy got his family’s favorite architect, I.M. Pei, to come on board, and they proceeded to change both blocks. Prospect was chosen because it was intact, beautiful, somewhat isolated and, most important, filled with strong and proud community-minded homeowners.

Pei didn’t do much here. They made access to the block limited, expanded the sidewalks, and added concrete seating, new lighting and landscaping.

The result was a park-like block that encouraged neighbors outside to congregate with each other. The changes to St. Marks Avenue were much more involved. For more on this project, please see my Walkabouts on the topic, Saving Bedford Stuyvesant Part 1, Part 2, Part 3 and Part 4.

The Superblock project remained only a pilot, and no more Superblocks exist in Bedford Stuyvesant. But it and the work of the Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation changed life in Central Brooklyn for many people. The block was further chosen by filmmaker Sidney Lumet as the location of Dorothy’s home in the movie The Wiz. The movie starred Diana Ross, Michael Jackson and Richard Pryor. Scenes were filmed here in 1978.

By the end of the 1940s, Shirley was still living on Prospect Place, teaching at the Mount Calvary Child Care Center in Harlem during the day, and going to Teacher’s College at Columbia in the evening. She worked at the center for seven years, while obtaining her master’s degree in early childhood education.

During that time, she met a young Jamaican immigrant named Conrad Chisholm. He was working as a private investigator at the time, and they fell in love. They had a big Jamaican wedding in Brooklyn in 1949.

It’s true that busy people always have time to do more in their lives, and Shirley managed to work, go to school, keep house and also get involved in politics. She joined the 17th Assembly District Democratic Club.

By this time, in the late 1940s and early ’50s, this predominantly Black district had all white officials, mostly career Irish politicians. The Democratic clubs elected the state senators, the assemblymen and the local city council member. They, too, were all white.

They had to have community meetings with their constituents, at the end of which they would open up their meetings to questions from the community. But many in this working-class immigrant minority community were too intimidated to ever ask questions, or demand things from their representatives. Plus they had to line up and approach the dais, like petitioners to the king. Well, Shirley wasn’t going to be one of them.

She stood up and asked questions, demanded answers, and made the elected officials and the club politicians sit up straight. The club tended to keep their women serving snacks and taking a back seat, but Shirley Chisholm was not a backseat kind of woman.

She took over some of the women’s committees and made the men address their concerns. It was her start in the contentious world of politics. Needless to say, she was not popular with the leadership of the clubs, but she gained the notice of a group of Black leaders in Bedford Stuyvesant who wanted to organize to send their own to the seats of power.

In 1953, Shirley Chisholm became the director of the Friend in Need Nursery School in Brooklyn. After a year there, she became the director of the Hamilton-Madison Child Care Center in Manhattan, a large institution in Harlem.

She remained there for five years, and then took a position with the city as consultant to the City Division of Day Care. It was 1959. She had taken a break from politics during this time, but working in and near City Hall had once again whetted her interest in political office.

In 1960, she and six other people founded the Unity Democratic Club, a political club whose purpose was to get Blacks and hispanics more involved and organized in politics, and to get Black and hispanic candidates elected to office, especially in their own districts. The Civil Rights Movement was in full swing, and Shirley and others felt that it was more than time for Black districts in the city to be represented by Black elected officials.

She decided to run herself, and was elected to the New York State Assembly in 1965. She was only the second Black woman to be elected to the New York State Assembly. She served until 1968, when she decided to run for Congress. During that time, she and Conrad bought their first house in Crown Heights, on Virginia Place, only two blocks away from her parents. Our walking tour’s third stop is this house.

3. 28 Virginia Place: The two small streets of Hampton and Virginia places were the brainchild of two Philadelphia developers named Charles C. Haines and Hames A. Campbell. Part of this land deal involved a hotel in Virginia Beach, Va., which must explain the names of these streets.

Haines and Campbell had the streets added to the street grid, between Kingston and Albany avenues at Park Place. This was in the early 1890s, when the neighborhood was gaining cachet as the “exclusive and posh St. Marks District.” These houses were on of two small enclaves designed in this area, marketed as exclusive buildings in a quiet setting.

The design of the houses would be a unique mixture of 50 houses, 23 three-story-and-basement houses, along with 28 two-story-and-basement homes, all designed by the same architect, all joining harmoniously in a two-block cohesive unit. Each block would contain fourteen houses, two three-story houses on each corner, and two in the center of the block, with the west side of Hampton Place only having eight houses. The houses were designed by Charles Betts.

The Philadelphians, unfortunately, went bankrupt, and Charles Betts and his family’s construction and development company took over and finished the project. The first of these attractive Renaissance Revival style houses went on the market in 1902.

28 Virginia Place, the house the Chisholms bought, is one of the larger houses, this one even more significant, as it is a corner house, sitting on the corner of Virginia and Sterling places. Today, it’s still in fine shape, and is a two-family house. The Chisholms lived here for about six years.

In 1968, the courts ordered a new election district to be created in Bedford Stuyvesant. Before that time, the huge neighborhood had been parceled up and included in surrounding white neighborhoods, which elected the representatives. Considering that Bedford Stuyvesant at that time encompassed parts of today’s Clinton Hill, all of Bedford, Stuyvesant Heights and Crown Heights North, up to Eastern Parkway, the old gerrymandered districts were even worse than they are today.

Both white and Black Brooklyn Democratic leaders vowed to send a Black politician to the U.S. Congress. Shirley decided to run, facing two other Black Democrats for the nomination. She won. She then ran against James Farmer, one of the greats of the Civil Rights Movement, an organizer of the Freedom Rides, and a co-founder of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE).

He was running as a Republican, in part because he said that the Democratic Party should not take the Black vote for granted. They had the same views on most other positions, and you would have thought that Shirley Chisholm would have lost, due to Farmer’s history and name recognition. But Farmer made one big mistake.

He told his Black audiences that Black women had “been in the driver’s seat” for too long in the Black community, and that the community “needed a man’s voice,” in Washington, not the voice of the “little schoolteacher.” Shirley went on the offensive.

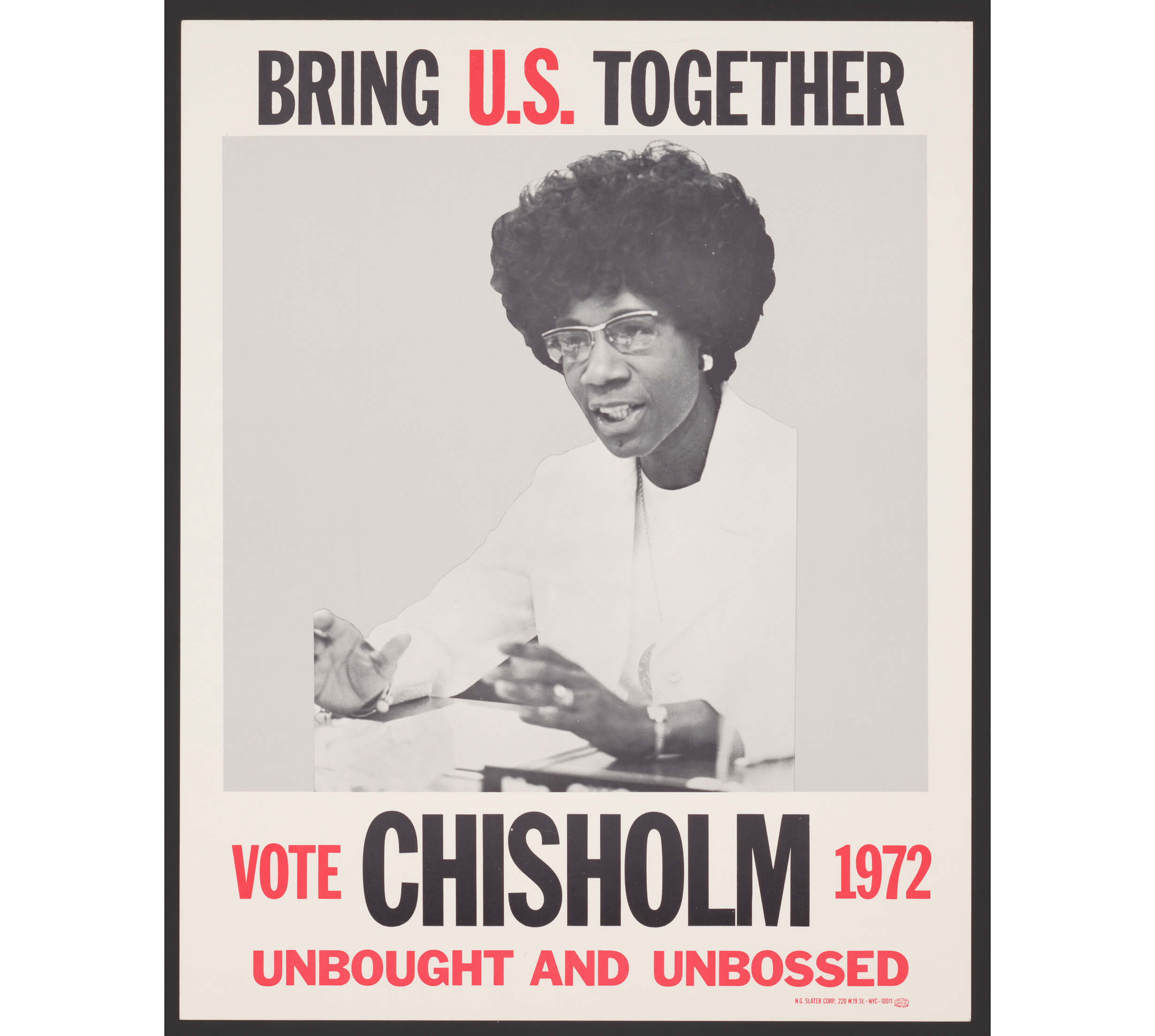

She told her audiences that her motto was “Unbossed and Unbought.” She explained that “there were Negro men in office here before I came in five years ago, but they didn’t deliver.” She could. She also used her fluency in Spanish to woo the large Puerto Rican community living in northern Bedford Stuyvesant. She carried the women, the Spanish vote, and the general Democratic vote. She won with 67 percent of the total vote.

When Ms. Chisholm arrived in Washington in January of 1969, she was the first African American woman to be elected to that body, and was one of three African Americans elected to Congress that year. She was also the only new woman elected that year.

Congress had heard about Shirley Chisholm, and they were not looking forward to this small, but very persistent Black woman from Brooklyn. Her first speech at the podium, on March 26, 1969, was a condemnation of the Vietnam War. Shirley Chisholm was just getting started.

When Congress convened in January of 1969, there was only one new female face among the men and women of the 91st Congress. She stood out for several reasons, the most obvious being that she was the only Black woman in the room.

She was also a small woman, slight of build, with big hair and thick glasses. She was not overly awed by the panoply around her. Shirley Chisholm had come to Washington to work.

She was representing a newly created and long overdue district in Central Brooklyn, that of greater Bedford Stuyvesant. Prior to this new district, Central Brooklyn had been gerrymandered into other larger districts with white majorities.

For the first time ever, a Black Congressman, in this historic case, a Black Congresswoman, was going to represent this community’s many needs in the halls of power. It was going to be an uphill battle. But 1969 was one of those years.

Today, we are very cynical about what goes on in Washington, and with good reason, but almost 50 years ago, it was a different place. There was more respect for Congress and its power to change the country for the better.

But in many ways, Congress was still the same. There was rampant cronyism, partisan in-fighting, powerful outside influences, racism, sexism and the good-old boy network. Shirley Chisholm had to fight her way through it all. And like her experiences in politics in Brooklyn, Shirley knew how to be effective, and how to work with the most unlikely of people.

This is the story of Ms. Chisholm’s political and personal life, and it’s also the third part of our walking tour of the places that had meaning to her in her hometown of Brooklyn.

Shirley was about to embark on her Congressional career after winning the 1968 election, so they hardly were settled in this home when she left for Washington. Conrad stayed in Brooklyn. He always said that he didn’t like the spotlight, and was quite content for his wife to be in politics and in the public eye.

He stayed home on Virginia Place during her early Washington years. When Shirley came home, the house must have been bustling with meetings with important local figures, friends and everyday folk.

Back in D.C., Shirley wasted no time in establishing her bona fides as someone who lived by her political slogan — “Unbossed and Unbought.” Her first speech on the House floor in March of 1969 was a condemnation of the Vietnam War. She vowed to vote against any defense appropriation bills “until the time comes when our values and priorities have been turned right–side up again.”

The real power in Congress lies in the committees to which one is appointed. Shirley Chisholm, a woman who had lived in Brooklyn for most of her life, and represented the ultimate in inner city communities, was assigned to the Committee on Agriculture, a very blatant message that she would be rendered useless.

She knew it, and was not happy about it. She came home and had a meeting with one of her constituents and an old friend, Rabbi Menachem Schneerson, the Grand Rebbe of the Lubavitch community, who lived only blocks from her house.

This remarkable alliance is not often talked about, and I would love to explore their relationship further. I think Rabbi Schneerson must have loved Ms. Chisholm’s chutzpah. The Lubavitchers and the West Indians had lived side by side in Crown Heights since the end of World War II, pretty much ignored by the rest of the city.

While the relationship had its tensions and cultural differences, both sides shared these streets in peace, and Shirley Chisholm was the elected representative of their district. The Grand Rebbe’s offices are our next stop on our walking tour.

4. 770 Eastern Parkway: Rabbi Schneerson’s office was located at 770 Eastern Parkway, between Brooklyn and Kingston avenues. It is a large, attractive Gothic Revival building that serves as the world headquarters for the Chabad Lubavitch movement, the largest of the ultra-orthodox sects of Judaism. The building was originally built as an apartment building in the 1930s, with medical and doctors’ offices on the ground floor.

In 1945, the building was purchased by the Chabad Lubavitchers for Rabbi Schneerson’s father-in-law, Rabbi Yoseph Yitzchak Schneerson. The building became the group’s main synagogue, a yeshiva, and home to the elder Schneerson. The younger Rabbi Schneerson had his office on the ground floor.

After the death of Rabbi Yoseph Schneerson in 1950, his son-in-law Menachem became the leader of the Chabad Lubavitch movement. This location became the world headquarters. As time passed, it became much too small to remain the main synagogue and yeshiva and the building was added to, and some of the functions of the organization moved to other nearby buildings.

By the time Shirley Chisholm and Rabbi Menachem Schneerson were working together, the Lubavitch movement was a powerful presence in Crown Heights and in Shirley Chisolm’s district.

When Shirley told the rabbi she had been shuffled off to the Agricultural Committee, she complained that the committee was irrelevant to her urban constituents. He told her to own it. He suggested that she use the resources of the Department of Agriculture and feed the people of the inner city and the hungry anywhere in the country.

She took his advice, and working with Robert Dole, expanded the food stamp program and established the WIC program, food for women, infants and children. Shirley always credited Rabbi Schneerson for the fact that babies and children would now be eligible for supplemental food.

Shirley Chisholm’s stay in Congress involved one cause and one fight after another. She was an ardent fighter for her causes of racial equality and equal rights for women, as well as for children’s issues. She didn’t like the games of Washington, and often refused to play them, gaining a reputation as difficult and not a loyalist.

She held the needs of her constituents as more important than the needs of the little subgroups she was being groomed for, and when that meant crossing the aisle to get a project approved and through Congress, then she crossed the aisle and worked with the Republicans who could get it done.

By 1972, Shirley Chisolm was one of the most visible and powerful members of Congress. She was one of the founding members of the Black Caucus in 1971 and that same year was one of the founding members of the National Women’s Political Caucus. She shocked constituents and Congressmen alike when she visited Governor George Wallace in the hospital after he had been shot. He later helped her get Southern support and votes on a bill that gave domestic workers the right to receive a minimum wage for the first time.

5. 1028 St. Johns Place: Back home, Shirley and Conrad had moved to a new home during her first term in Congress. It was only a block away from their Virginia Place home, at 1028 St. Johns Place, between Brooklyn and Kingston avenues. 1028 St. Johns Place is a single-family neo-Tudor row house built in 1912.

This part of Crown Heights is anchored by the beautiful Roman basilica-style church of St. Gregory the Great, built in 1915. By the ‘teens, the grand rows of upper-middle class townhouses were no longer being built. Smaller homes and two-family houses were going up in this increasingly middle-class white ethnic neighborhood, now populated by Jewish, Italian and Irish homeowners.

These houses were being built in the popular Colonial Revival, neo-Tudor and Medieval styles suburban home styles. This group of houses that includes 1028 St. Johns are neo-Tudors.

The house is narrow, only 16.5 feet wide, but feels larger inside, because of a more open floor plan. Designed for the new American family without servants, the house has a living room, dining room, kitchen, and perhaps a powder room on the ground floor, and bedrooms and the main bathroom above. Like its suburban cousin, the houses also have garages in the back, accessible by a private alley.

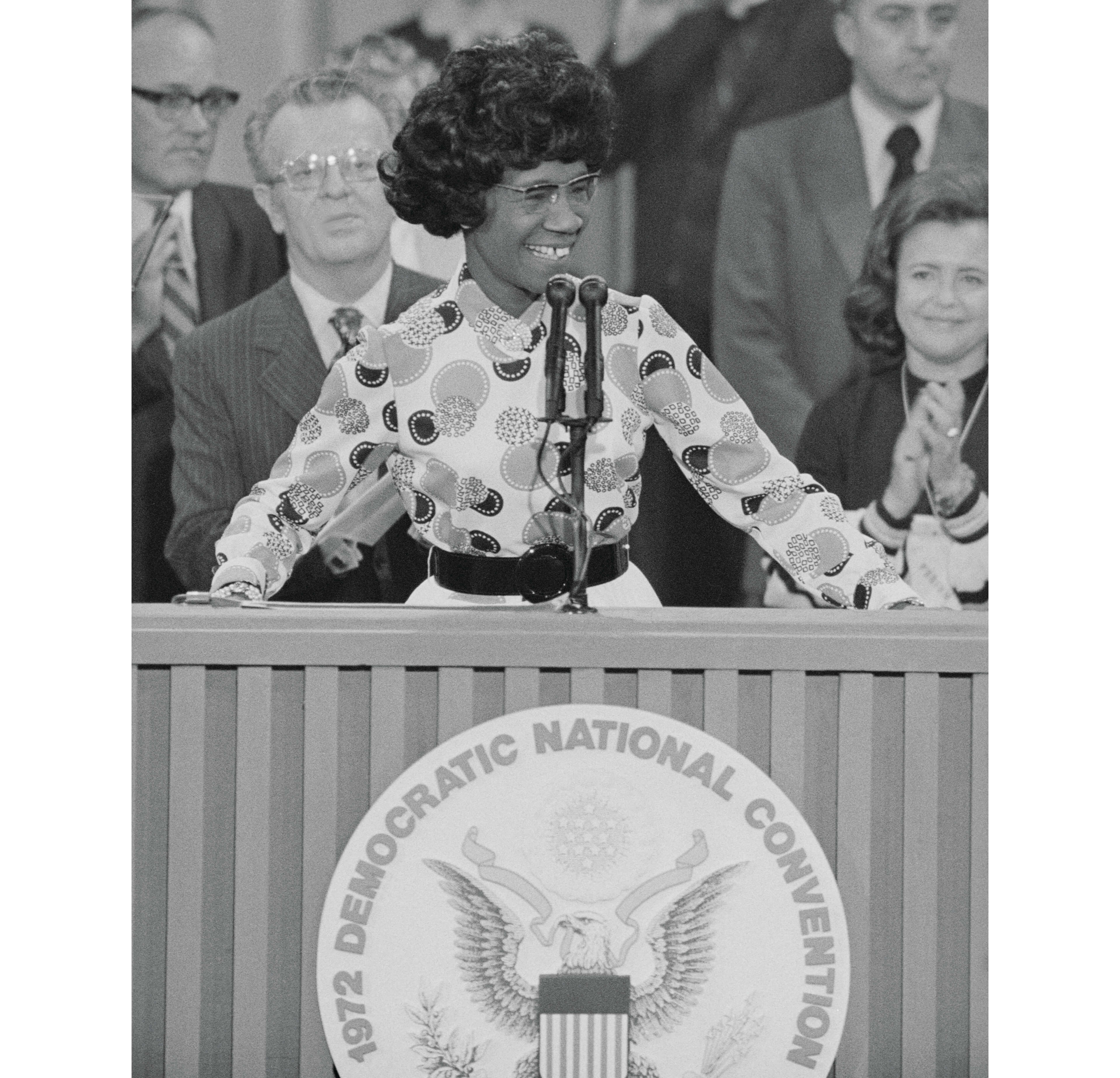

In 1972, Shirley decided to run for president of the United States. She received little attention from most of the Democratic Party, which considered her a symbolic fringe candidate. Sadly, she received even less help from Black male Democrats. She always said that she had encountered more impediments to her career from her being a woman than she did from being Black.

Within many segments of the Black political leadership, she was considered too strident, too pushy and not respectful of their leadership. Many considered her an emasculating matriarch, a quality that was often mentioned in the press.

The label bothered her greatly, and she said once, “They think I am trying to take power from them. The Black man must step forward, but that doesn’t mean the Black woman must step back.” Conrad Chisholm didn’t have a problem with her candidacy, and supported her unequivocally.

The couple ran their campaign from the house on St. Johns Place, with political strategy meetings taking place here throughout the run to the Democratic primary.

Central Brooklyn had a lot of buildings that had originally had other functions when built, but had turned into catering halls, nightclubs and gathering spaces. Shirley and her campaign used the largest of these to hold rallies, and also took her campaign across the city and in several key states.

6. 1147 Eastern Parkway: The next stop on our tour was a former mansion at 1147 Eastern Parkway, a recent Building of the Day. This Colonial Revival mansion is located five blocks down from Lubavitch World Headquarters, our previous stop.

1147 Eastern Parkway was purchased by Conrad Chisholm and converted from a Jewish social and political club into an events space.

7. 1391 Bedford Avenue: Another rallying place for the Chisholm campaigns was the Bellrose Ballroom, a former automobile showroom, located at 1391 Bedford Avenue, in the triangle between Rogers and St. Marks avenues.

The Bellrose has started out as one of the many automobile showrooms built along Bedford Avenue, when it was known as Automobile Row. The building was built in 1918, and was designed by architect Henry Nurick, with a showroom on the ground floor and separate offices above.

Upstairs became the local branch of the Motor Vehicles Department during the 1930s, another indication of the size and importance of Automobile Row. By World War II, Automobile Row was in decline, and the building became a supermarket, and finally, in the 1960s, the Bellrose.

Shirley Chisholm held rallies here in both her Congressional and presidential runs for office. The Bellrose was lost to taxes in the ’80s, and has been bricked up ever since. It now belongs to nearby Washington Temple.

Shirley Chisholm did not even come close to winning the Democratic Primary in 1972, but she received several hundred thousand popular votes and 28 electoral delegates at the primary. She was the first serious female and African American candidate for president.

She paved the way for Jesse Jackson’s later run, and finally Barak Obama’s successful election. She was also an inspiration for Geraldine Farrarro and all of the women who followed her, a list that now includes Kamala Harris.

After the election, Ms. Chisholm went back to Congress, where she continued to push for the end of the Vietnam draft and the war, as well as for programs for the inner cities, women and children. She became one of the most visible and effective members of that body during her tenure. Her marriage to Conrad fell apart, and they divorced in 1977.

She later married Arthur Hardwick Jr. who had been a fellow New York State Assemblyman with her years before. He lived in Buffalo, and Shirley sold her house on St. Johns Place and moved there with him.

1028 St. Johns was sold to Carlos Lezama and his family. He was one of the original organizers of the world famous West Indian Day Parade, which dances along Eastern Parkway on Labor Day. The house went from the seriousness of politics to the equally serious job of organizing this huge event.

The house is still in the Lezama family, and is now the Carlos Lezama Archives & Caribbean Center, dedicated to Mr. Lezama, the parade, and Shirley Chisholm and her history and legacy.

By 1982, Shirley had grown weary of fighting. Ronald Reagan had become president, and the liberals in Congress were going in a direction she did not like. Her husband, Arthur, had had a serious accident, so she decided to retire to take care of him, and pursue her agendas outside of politics. She was immediately hired by Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts.

She taught there from 1983 to 1987. She was also a visiting professor at Spelman College in Atlanta. Arthur Hardwick died in 1986.

Shirley Chisholm spent the rest of her life on the lecture and speaking circuit. She told college students across the country to expand their horizons and avoid polarization and intolerance. “If you don’t accept others who are different, it means nothing that you’ve learned calculus,” she said.

She moved from the Buffalo area to the warmth of Florida in 1991. In 1993, President Bill Clinton wanted to appoint her as ambassador to Jamaica, but Shirley was not well enough to serve. Over the next few years she suffered several strokes, and died in 2005 on New Year’s Day. She’s buried with Arthur Hardwick in Forest Lawn Cemetery in Buffalo, N.Y.

Her legacy is great, both here in Brooklyn, and nationally. She spent her life breaking the norms and the rules in a passionate pursuit of justice and social equality for all people, especially those in poverty.

Many other honors have been bestowed on her, as well. There is so much more nuance to her story than what was told in this three part essay. She was a remarkable woman, one who remained throughout her life Unbossed and Unbought.

(Research for this series came from newspapers, official biographies from various different sources and a great book, Paving the Way for Madam President, by Nicola D. Gutgold. Architectural information has come from my own research and that of the Landmarks Preservation Commission for the Crown Heights North Historic District, which includes all three of Shirley Chisholm’s residences in its boundaries.)

[Photos by Susan De Vries unless noted otherwise]

Related Stories

- Brooklynite You Should Know: Shirley Chisholm

- Walkabout: Saving Bedford Stuyvesant

- Taking a Risk During a Building Boom in 19th Century Crown Heights

Sign up for amNY’s COVID-19 newsletter to stay up to date on the latest coronavirus news throughout New York City. Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment