A Brooklyn Tale: Romance Author Alyssa Cole Sets a Thriller in Brooklyn

Award-winning author Alyssa Cole talks about how she became a writer and the thought process behind her latest book, a bestselling thriller about the scourges of gentrification and racism.

Photo by Susan De Vries

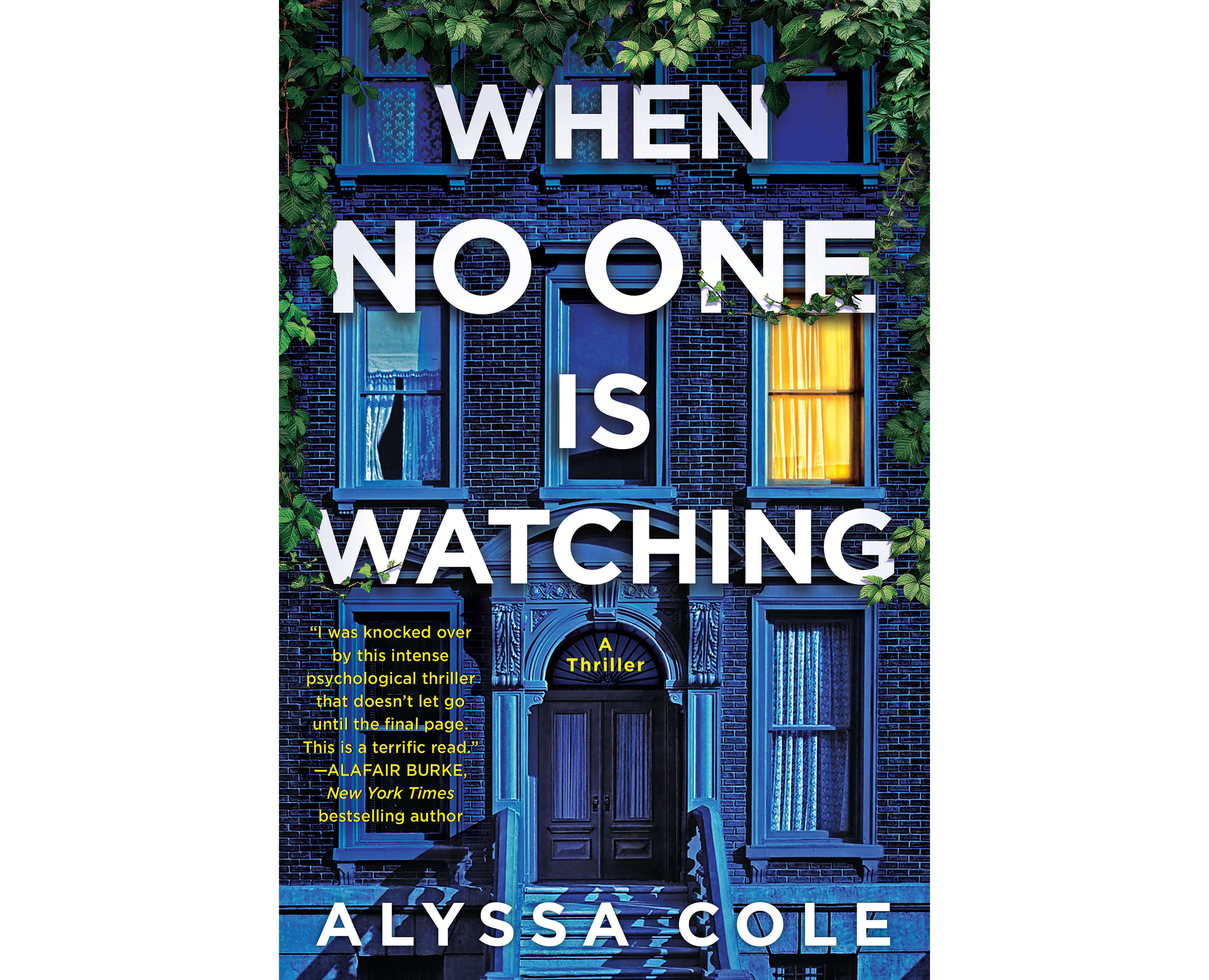

Alyssa Cole’s latest book, “When No One Is Watching,” is a thriller about racism and gentrification set in Brooklyn. Shifting back and forth from the point of view of a lifelong Black resident of a coveted brownstone block to that of a white newcomer, the story skillfully incorporates bits and pieces of the real Brooklyn: stoops, bodegas, neighborhood history tours, construction sites, even an ancient shuttered hospital and a mysterious family photo album found on the curb.

It’s set in an unspecified locale “vaguely around the Crown Heights/Bed Stuy border near Weeksville,” Cole told Brownstoner. Reminiscent of Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery” in its effect, the book successfully elicits the terror of real-life systemic racism.

After reading the tale, published by William Morrow in 2020, readers may question their grip on what is real and what is fiction. Known for romance novels, Cole moved to Brooklyn after college and now lives in Martinique.

I could not put the book down and I find it incredibly chilling and haunting. By the end, it no longer seemed entirely fictional. What was the inspiration for the book, and did you have a specific goal in telling this story?

I spent my childhood in New York City and across the river in Jersey City, and most of my adult life in Brooklyn, so I’d been seeing gentrification for years. Before I moved, I had seen it really ramping up in my neighborhood. It was just kind of something always in the back of my head, seeing how things were changing in similar ways everywhere, and wondering where do displaced people go. So I had the opportunity to work on this thriller and take all these ideas I’d been ruminating on for years, some of which I’d started to explore in a previous romance set in Scotland, “A Duke By Default.”

You lived in Crown Heights, Park Slope, Williamsburg and Bed Stuy from 2005 to 2014. What were some of the changes you saw during your time in Brooklyn?

Each time I moved I could see the rent prices [increasing] and how impossible it was becoming to find a place. And even though I wasn’t making much money, I was making more than people working full time at minimum wage. I was always wondering how people were able to make it work.

The book is set in and around Crown Heights and Bed Stuy, close to the historic area of Weeksville. Why did you select that particular location?

Because I think Brooklyn is emblematic of gentrification. That particular location — once I decided Sydney would be working on this historical tour, I thought it was also this great spot because it has this particular history people don’t know about. I lived in that neighborhood and had no idea Weeksville was there — and I love history. It seemed like a way to talk about this community and also the way entire neighborhoods and the hard work of the community can be erased. It becomes this casualty of change.

Is the hospital in the book based on a real building?

I mostly made it up. It’s a mash-up of various hospitals in Brooklyn and Jersey City, past and present, and the lore that can pop up around those types of places. There are also elements of the Jehovah’s Witnesses buildings along the waterfront and some other buildings from Brooklyn history, but saying why would spoil some [surprises].

As I was reading the book, I noticed some plot twists that actually happened in real life, some of which we wrote about on Brownstoner over the years. I don’t want to give away too much of the story but, for example, one of the characters finds a discarded family photo album on the street. Can you tell us a little bit about how and why you worked real-life events into the book?

I remember seeing an article about the photo album years ago and it was something that stuck with me, the idea of someone’s history just being out in the trash. I incorporated it because both Theo and Sydney are characters who are looking for something but they don’t know what they are looking for — and perhaps clinging to things that are not particularly healthy. Theo at the beginning of the book isn’t particularly aware of the Black community around him even though he has this [photo album]. He’s kind of projecting his own thoughts onto the people in the photo album and Sydney. I thought it would play into his character and the way the neighborhood changes and the past gets thrown out with the trash. I couldn’t think of a better way of showing that.

Did you go on any neighborhood tours? Did you come to Brooklyn to do research for the book?

I didn’t go on any tours; a lot of it was from when I lived there. I did go back to Brooklyn to visit Weeksville and see the houses and the center and how things had changed in the time I had been gone. Before I went to Brooklyn, I saw there was a tour by Suzanne Spellen, who is a Black woman who does walking tours, and is actually [Brownstoner columnist] Montrose Morris, whose work was so important to me as I was researching the book. So I was able to reach out to her and talk to her. I said, “This may sound wild but I’m writing a book about a Black woman who gives tours in Brooklyn and I swear it’s not based on you. Would you be interested in talking to me?” She gave me some great insights. It was really great talking to someone who knows Brooklyn so well.

I hear a rooster.

They start to make noise any time I get a phone call, have a Zoom…

The book touches on a lot of experiences and issues that have been in the news lately thanks to the George Floyd protests. Can you tell us a little bit about that?

So this past summer [2020] has been really — I’ve been telling people this has been the worst ad campaign ever, literally seeing stuff in the news and that’s like the thing that happened in chapter whatever. Amy Cooper calling the cops on the Black birdwatcher, the George Floyd stuff, the uprising, the Karen syndrome that was sweeping the nation and captured in so many videos. It was this weird thing. I didn’t pull these things out of the ether, they existed and I wanted to incorporate them into this book because sometimes I feel — this was something I was aiming for in the book — these are experiences that are fairly common for Black people but so bizarre that they are sort of like horror and gaslighting. If you tell people who have never experienced something like that, it’s difficult to believe on some level. Why would someone call the police when you haven’t done anything, or clutch their purse when you walk by — all these micro aggressions and flat out aggressions that can become normal and add to the stress of daily life. I wanted to put these things in the book, and over the past summer things just kind of exploded and they’re being shown in the news more and being recorded more and showing people these things happen all the time. And, also seeing the behavior of police when they’re asked the most basic thing, like “can you stop killing Black people?” and their response is to start beating everyone up. I wanted to talk about those things in the book, and those things are moving to the forefront of reality and people’s minds.

It’s horror, but it’s not fictional.

It’s true. One of the things I wondered when I wrote the book is if people will say the ending is too out there. It didn’t feel particularly out there to me. I know it was obviously heightened. It didn’t feel so far outside the realm of possibility, and then seeing all this stuff going on in reality, it’s like yeah, OK, why wouldn’t this happen?

How did you become a writer? Did you always know you would write?

I always wanted to be a writer. I didn’t always know I would become one. I was able to finish [my first book, “Eagle’s Heart”] because of National Novel Writing Month. It’s an event where people all over the world try to write a full manuscript of 50,000 words in 30 days. Obviously you have to go back and revise. It’s to get the story out and show you can finish something.

You are known for writing romances. Why did you choose to write a thriller?

I like trying different things. I grew up reading thrillers and horror novels and felt like it would be a fun challenge to tell the gentrification story through that lens as opposed to romance. I still have to get my romantic elements in there. I wanted to focus a bit more on the horror instead of the happily ever after.

Editor’s note: A version of this story appeared in the Spring/Summer 2021 issue of Brownstoner magazine.

Related Stories

- Growing Pains: Park Slope-Based Cartoonist Adrian Tomine Contemplates Life and Work

- Greenpoint Author Melissa Rivero’s Journey Through the Past

- Jonathan Lethem Comes Home

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment