The Weeksville Heritage Center Looks to the Future With a Focus on Art and Community

Set on land that was once part of one of the largest free black communities in the United States in the 19th century, the institution is “uniquely situated” to address issues of race, equity and social justice, according to its new director.

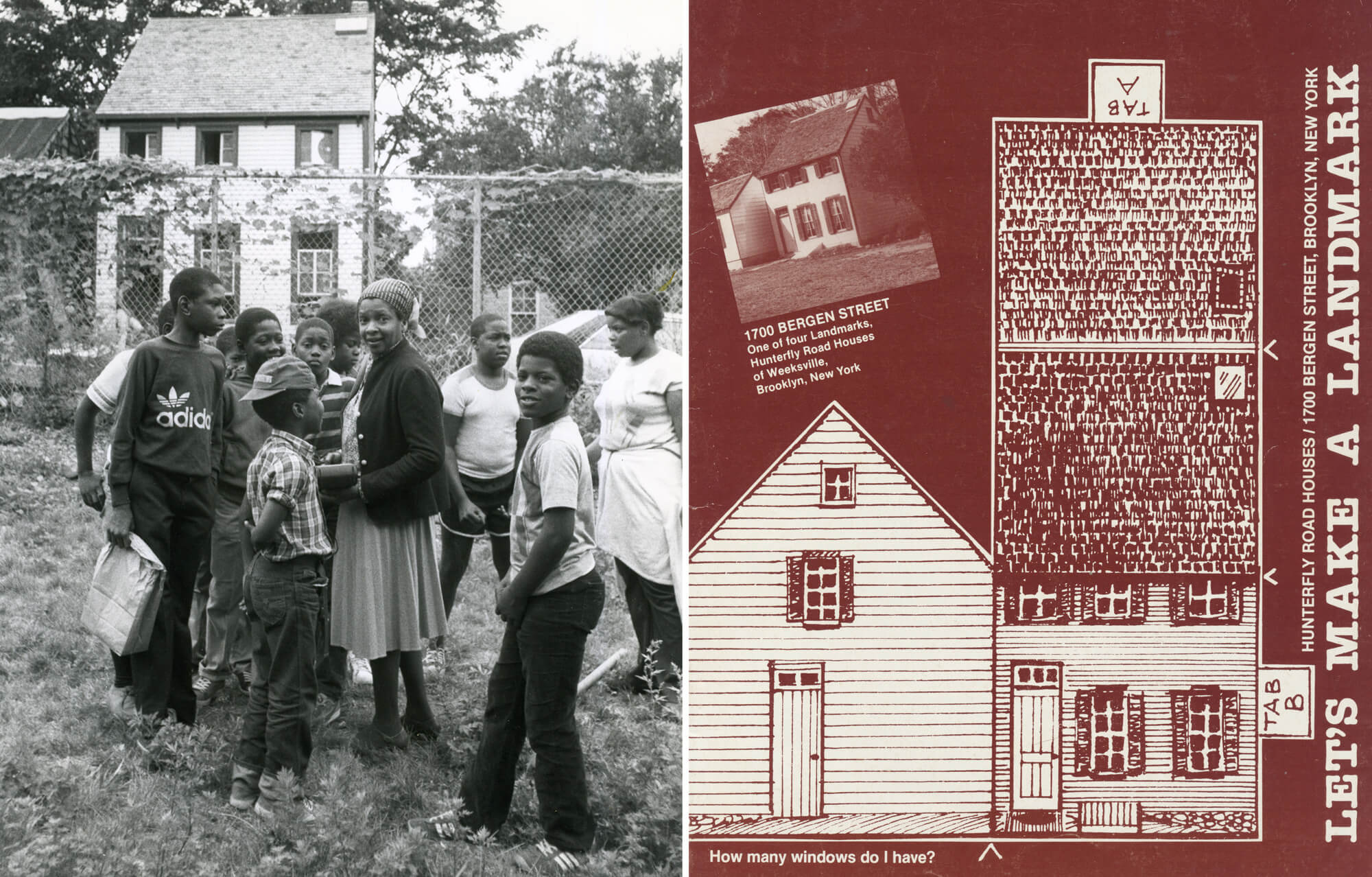

The Hunterfly Road houses in 2018. Photo by Susan De Vries

In 2019, the Weeksville Heritage Center was in danger of closing. Situated on land that was once part of one of the largest free black communities in the United States in the nineteenth century, the institution was in trouble due to rising operating costs and issues with fundraising. Through crowdfunding, the group was able to raise nearly $300,000 to stay temporarily afloat. More was needed. In March 2020, right as the pandemic was forcing most of New York City into lockdown, Weeksville was added to the city’s Cultural Institutions Group, which opened up access to additional funding from the city and sparked a renewed focus within the nonprofit.

But part of that renewed focus also stemmed from the increasingly vocal conversations about our relationship to race in the United States. In May 2020, the murder of George Floyd by a white police officer in Minneapolis set off a chain reaction of protests throughout the entire country. Questions that once remained in the background were being brought to the surface, questions that Weeksville was appropriately positioned to address.

“Really, if we look at the history of Weeksville, it’s uniquely situated to address the issues we’re dealing with right now—race, equity, social justice,” says Raymond Codrington, an anthropologist and arts administrator who joined the institution as president and chief executive officer in April. “Those are the tenets under which Weeksville was created. It’s not even an update of the story. It’s just telling the story.”

Founded by and named after James Weeks in the 1830s as a free black community in an area now known as Crown Heights, by the 1850s Weeksville had about 500 residents, along with churches, schools and businesses. The community even had its own newspaper, called The Freedman’s Torchlight. But post-Civil War, as the modern street grid and real estate development expanded across Brooklyn —including the construction of the Kingsborough Houses, located right across the street, in 1941—Weeksville began to slowly disappear. By the 1960s, it had largely been forgotten.

But in 1968, the discovery of four historic homes on Hunterfly Road led to a newfound resurgence of interest in Weeksville. Historian James Hurley, along with Joseph Haynes and students from Pratt, who found the homes during a research project, helped organize local groups around saving the houses, which were in danger of being demolished. In 1970, the four homes (one burned down in the 1990s, later to be reconstructed) were designated as landmarks by the Landmarks Preservation Commission.

Their work also led to the eventual formation of the Society for the Preservation of Weeksville and Bedford Stuyvesant History. Under the leadership of Joan Maynard, an artist, community activist and preservationist, the group, which later became the Weeksville Heritage Society, helped bring continued attention to the existence of the homes and their planned restoration.

“She was a one-woman dynamo,” writes Judith Wellman in “Brooklyn’s Promised Land: The Free Black Community of Weeksville, New York,” published by NYU Press in 2014. “She gave slide shows to local schoolchildren and community groups, directed tours and organized programs. Most of all, she raised money, continually.”

Until her retirement in 2001, Maynard and others worked tirelessly, often against all odds, to make sure the Hunterfly Road houses were restored. Under the leadership of Pam Green, who took over for Maynard, an award-winning modern museum building was constructed on the center’s grounds and opened in 2014, allowing the institution to expand its programs, add offices and provide more space for events and exhibitions.

“This historically significant site is the kind of place any artist conducting our kind of research-driven work dreams of,” says Mendi + Keith Obadike, who previously served as artists-in-residence at Weeksville with their 2018 project, ‘Utopias: Seeking For A City,’ which was installed in one of the Hunterfly Road houses. During the run of their installation, they asked viewers to leave a comment on the idea of utopia. “So many people took the opportunity to say what a special place Weekville was and is.”

And the future continues to look bright for the Weeksville Heritage Center. During a recent conversation at the organization’s offices, Codrington, who previously headed up East Harlem’s Hi-ARTS, talked about the importance of the center and how, as a historic site, the organization is equipped not only to respond to the present moment but think about the future. “We don’t want to lose anybody, but we definitely want to push the boundaries,” he says.

What do you think people still don’t understand about Weeksville?

I think the fact that such a significant free black community exists in an urban setting, in the middle of the neighborhood. A common thing people say is, first, “I didn’t know this was here.” And then, “Why didn’t I know this was here?” I can tell you about Weeksville, you can read about it and go to the website. But you have to come here. You have to see what it means to have a historic community right next to public housing, right next to a contemporary art center, and see how all those interact, and see that that is the fullness of Weeksville.

And the location of the Weeksville Heritage Center matters.

This neighborhood is an asset, one of our biggest assets. And we’re able to do this kind of work among people that look like the leadership, look like the staff that are doing programs that allow committee members to see themselves represented in the work. At the same time, it really is accessible—it’s really a couple more train stops away from Downtown Brooklyn.

In what ways is Weeksville looking to be more than a historical site or cultural institution?

Weeksville is able to speak to social issues, like the notion of being a food desert. Historically, there was farming done at Weeksville. But the idea that a cultural institution can provide a service around fresh produce, people don’t realize there is a service component to Weeksville. We do arts, culture, history, but this is a vaccination site, a polling site.

Does the community reach out with things they need and maybe Weeksville can provide?

I think a lot of community members want space—space to convene, spaces to discuss issues that are important to them. They want to see exhibitions, programming that deals with the issues they are dealing with. A lot of the time when I’m here people will stop by. “Can I talk to the president? Can I talk to who’s in charge here?” You know, the sense of ownership and engagement people have with the institution is really interesting and unique. I haven’t really seen it in other places. I’ve worked at other institutions where there was strong alignment with the community, but this is different. They want tools to tell their own stories, say genealogy, oral history workshops. Notions of culture, history, representation—they want to see that here and done in ways that are accessible to them, that they understand. They want to feel like the institution sees and hears them.

You mentioned ‘pushing the boundaries’ at Weeksville. What kind of projects are you envisioning for the institution’s future?

I love the idea of public art installations. The outdoor space here is calling me. But also, work that looks good both within the gates [at Weeksville] and outside, from the street. I’m interested in building out the artist-in-residence program and, within that, some art that’s a little more performative, slightly more abstract. Activating more of the spaces here, like using the meadow for installation, I would love to develop an artist studio—there’s a space here that I have my eye on, where artists can be on site and create. Those are just some of the things I’m thinking about. But part of it is the kind of artist and the curation of the artists.

In 2019, Weeksville joined 33 other venues as part of the Cultural Institutions Group. Why was this important for Weeksville?

It’s important for an institution like Weeksville to be part of the CIG because of the work we do, our history and the community members who have supported us. To have an institution that is centered around a historic site, it’s important to be seen as a peer with the other CIG institutions. To have us and our story represented in that group says a lot about how the city sees the importance of a place like Weeksville, populations like Weeksville, at the size of Weeksville. Why shouldn’t we be there? Why shouldn’t we be represented alongside the large cultural institutions? Black history needs to be right next to them as pillars of how we represent culture in this city.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

Editor’s note: A version of this story appeared in the Fall/Holiday 2021/22 issue of Brownstoner magazine.

Related Stories

- The Inspiring Story of Weeksville, One of America’s First Free Black Communities

- Set Back the Clock With a Visit to the Historic Interiors of Weeksville (Photos)

- Block of Buffalo Avenue to Be Renamed in Honor of Joan Maynard

Email tips@brownstoner.com with further comments, questions or tips. Follow Brownstoner on Twitter and Instagram, and like us on Facebook.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment