From Dutch Farmland to Romanesque Revival Row House: A History of 68 Midwood Street

Designed by architect William M. Miller and completed circa 1900, the house is part of a transitional Romanesque Revival and neo-Renaissance row that was one of the earliest rows to go up in the Lefferts Manor district.

By Suzanne Spellen (aka Montrose Morris)

The creation of modern day Lefferts Manor in Prospect Lefferts Gardens goes back to the Dutch and, in particular, the Lefferts family. In 1609, Henry Hudson sailed his ship, the Half Moon, into Coney Island Bay. After some initial exploring, he found a large river and sailed north, thinking he had discovered the passage to the Far East.

He got as far north as what is now Troy, N.Y., and realized he was wrong. Turning around, he sailed back down the river that now bears his name and back to Holland, where he reported back to his employers, the Dutch East India Company. He told them of a fair land, full of game and rich farmland, ripe for colonization and conquest. The era of the Dutch, who permanently shaped the history of New York, had begun.

See the listing for 68 Midwood Street for more about the house and its availability >>

The Dutch didn’t land with huge armies to conquer, like the Spanish. They did it through trade, purchase and colonization. They “bought” the land from the indigenous peoples, settled up and down the Hudson, and established New Amsterdam at the mouth of the Hudson River. On the other side of the East River, six towns were established in what is now Kings County. One of the original towns, Midwout, was also called “Vlacktebos,” and from this comes the English word “Flatbush.”

Flatbush Avenue was established on a previously existing Native American trail that stretched north from Flatlands to the banks of the East River. To the north lay the town of Breukelen, to the south, Flatlands, and in the middle, Midwout, aka the “middle woods.” In 1664, the Dutch territories of New Netherlands were won by the British in a naval campaign. The towns of Brooklyn became part of the province of New York, named for the Duke of York. In 1683, those towns were established as Kings County.

Thirty years before the British takeover, Dutch settler Han Hansen Bergen purchased several hundred acres near the town of Midwout. Much of his land makes up modern Flatbush. In 1660, a farmer named Leffert Pietersen Van Haughwout came to America and settled in the area. His name in Dutch literally translates “Leffert, son of Peter, from Haughwout.” (Haughwout was the name of a town.) He bought some land near New Lots and established a homestead.

In 1692 he was appointed constable of Flatbush, and in 1703 became one of the assessors of the town and a member of the grand jury. Leffert Pietersen married Aukersie Van Nuyse, the daughter of another Flatbush farmer, and they proceeded to have 14 children, 12 of whom were male. Although it was the Dutch custom to be named after one’s father, or the town from whence one came, after a generation or two in America, the family surname was permanently changed to “Lefferts.”

Patriarch Van Haughwout and at least two of his sons moved north to Bedford. That branch would eventually own most of the land that makes up Bedford Stuyvesant, Crown Heights North, Weeksville and more. Other family members ended up in Pennsylvania, where the Lefferts family remains strong.

By the Revolutionary War, the Flatbush branch of the family had grown as well. In 1776, at the beginning of the war, the British invaded Brooklyn, culminating in the Battle of Brooklyn. Before that fight in August of 1776, American troops burned down the Lefferts homestead to prevent the British from acquiring it.

After the war, great-grandson Peter Lefferts rebuilt the house and expanded his lands. He was now one of the wealthiest men in Kings County, with a 240-acre farm, and a large household that included eight family members and 12 enslaved people of African descent.

In 1778, Peter Lefferts was a delegate to the state convention in Poughkeepsie, when New York ratified the United States Constitution. He was also one of the original contributors and trustees of Erasmus Hall. He died in 1791, and the estate passed to his 6-year-old son, John.

John Lefferts grew up to become a congressman and a state senator, serving between 1821 and 1826. He was well regarded by his peers and in the press and was known as “Senator John” to distinguish him from the other family members named John. He had two children, John and Gertrude. She would later marry into another important Flatbush family, the Vanderbilts.

Both John and Gertrude were devout Christians, with long histories of church founding and charitable work. John was also quite a businessman, and was on the board of the Brooklyn Bank, which his family had established, and was a trustee of the Long Island Insurance Company, the Long Island Loan and Trust, Flatbush Gas Company, Flatbush Water Works Company and the Brooklyn Safety Deposit Company.

This John Lefferts married Eliza J. Lefferts Lefferts, a distant relative, and the couple had four children who lived to adulthood. John Lefferts Jr. was the eldest, followed by James, Phebe and Robert. There were also several more children by John Lefferts’ second wife, after Eliza died in 1867. The story of 68 Midwood revolves around John Jr. and his brother James.

Flatbush became a popular suburban retreat after the Civil War, especially after the opening of Prospect Park in 1867. The land closest to the park received immediate attention. Local press, photographs and maps of the area show that this part of town was seen as a suburban frontier of sorts, a gateway to the countryside and the pleasures of the Coney Island shores. The maps and photographs show large houses, including the Lefferts homestead, on spacious grounds stretching along Flatbush Avenue as well as the side streets.

Flatbush became a part of the City of Brooklyn in 1894, by which time developers were already looking at the lands for urban development. Improvements in trolley and train public transportation made it possible to live in Flatbush and easily commute to a Manhattan job. Many of the local mansion dwellers knew their estates were more valuable as developable land. John Lefferts knew that too, and had his estate surveyed and plotted out. After his death in 1893, his children began looking at development options. John’s second son, James, would take the lead.

The Creation of Lefferts Manor

In 1893, James divided a section of the farm into 600 lots to be developed as a well-to-do residential development called Lefferts Manor. The Manor extended from Lincoln Road to the north, Flatbush Avenue to the west, Fenimore Street to the south and Rogers Avenue to the east.

The family also sold other land to developers in the neighborhood, outside of Lefferts Manor itself. Although residential development outside of those boundaries took place at much the same pace and time period as the Manor, Lefferts Manor was special. It was protected by an ironclad covenant written into the neighborhood’s founding by James Lefferts.

James set down a very specific covenant to restrict anything he felt was inappropriate to this endeavor. Most famously, for homeowners today, Lefferts instituted a single-family home restriction. There would be no two- or three-family homes, no apartment buildings within the Manor, no rooming houses, and no dividing up of single-family homes into multiple units. All commercial ventures would be placed outside of the boundaries of the Manor, as well.

Deed restrictions were a way of assuring a “certain kind of neighborhood” and by extension, one for only a certain kind of owner. In this case, a solidly middle to upper-middle class owner. Lefferts Manor was to be eight blocks of single-family housing, creating an uncrowded suburban enclave within a growing city. There would be no issues or concerns with tenancy or boarders. Lefferts advertised that the houses would be of “the highest quality in construction and workmanship.”

The deed also prohibited stables, pigpens, forges, iron foundries, fertilizer, gunpowder, saltpeter, candle, soap, ink, glue and varnish factories, as well as tanneries, breweries, hospitals, theaters, apartment buildings and tenements. There were also rules regarding the placement of fencing.

Lefferts mandated that the houses be at least 14 feet from the curb, be built of brick and stone, with bay windows and bow fronts projecting only 3.5 feet beyond the 14-foot setback. They had to be constructed at a cost of no less than $5,000, which was above the average for housing at that time.

As Lefferts was planning the Manor, the land he sold outside of those eight blocks was also being developed. Suburban-style Queen Anne and Free Colonial-style frame houses began going up in the 1890s. They were followed by rows of Renaissance Revival masonry row houses beginning in 1895.

As the 20th century progressed, more row houses were built in the larger neighborhood, most of them two-family houses, as well as six-story apartment buildings. By the Great Depression, large apartment buildings lined many of the nearby streets, especially on the corners, and facing Flatbush, Bedford and other avenues, with construction moving eastward.

Flatbush Avenue, which just was outside of the Manor, developed as a major commercial street, with all of the shops, theaters, tenements and all of the other establishments James Lefferts managed to keep out of his enclave. The mansions in the area disappeared, replaced by apartment buildings with storefronts on the ground floors.

Development started in earnest in the Manor between 1897 and 1899, when 160 houses were built along Lincoln Road. Development halted in 1903 during a serious financial depression called the Panic of 1903 but was up and running again by 1905. The period between 1905 and 1911 saw the largest number of houses built, totaling 507 homes. Most of these were Renaissance Revival-style stone-faced row houses in both brownstone and white limestone.

In 1918, the Lefferts family donated their farmhouse on the corner of Flatbush and Maple to the City of New York, and an apartment building was planned for the intersection. The city moved the house to Prospect Park, where it now operates as a house museum near Flatbush Avenue, Ocean Avenue and Empire Boulevard.

Development ebbed and flowed again. Between 1915 and 1925, 87 more houses were built, almost all red or soft golden brick Colonials or Tudors, including some larger freestanding Colonial Revival homes on large lots. The last empty lots were filled around 1927, with the very last house finished in 1950.

James Lefferts was very serious about his covenant. Between 1897 and 1915, as chairman of his board, he sued at least four different developers who were building in the Manor over issues regarding his restrictions. After James Lefferts’ death, the Lefferts Manor Association took up his mission with equal zeal and used the court system when needed to uphold the single-family restriction in the neighborhood.

While some could perceive this restriction as a threat to the idea that one should be able to do what one wants with one’s property, the case can also be made that Lefferts Manor always declared quite openly that this restriction existed and was backed up by law. If you wanted a house that you could subdivide, you could buy one outside of the eight blocks of the Manor. The surrounding blocks held plenty of opportunities. The Manor was special.

The Development and Marketing Genius of William A.A. Brown

Just because a sponsor creates a development neighborhood and has some houses built on it does not mean people immediately rush to buy, covenants or no. As James Lefferts began seeking experienced developers to buy and build, he was confronted with more than a little hesitation.

There wasn’t much around at the time. Flatbush was still lined with large houses, not stores and businesses. The blocks surrounding the Manor were slowly being built on, but if one were to visit the site in 1896, there were only scattered houses, with the initial groups of row houses being built on largely empty blocks. Selling the Manor would take time and patience. It would take a professional. William A.A. Brown was that man.

Brown was born in Brooklyn in 1856, and his family moved to Flatbush five years later. The family manse was a large estate on the park side of Flatbush Avenue. Much later, after his many successes, he built the largest private greenhouse and gardens in Brooklyn on the expansive grounds of his home. Brown made his initial money in banking and was described in the papers as a “successful capitalist.”

Before his real estate ventures in the Manor, he was best known in Brooklyn as a brewer. He had been with T.C. Lyman & Co., a very successful Manhattan ale producer, and then became the president of the Williamsburg Brewing Company. In 1884 he led a group of investors that purchased the Bedford Brewery, on Franklin Avenue, Dean and Bergen streets. The brewery had been founded in 1849 and at the time of their purchase was the tenth largest of Brooklyn’s 47 breweries.

Brown loved his new acquisition and was determined to grow it and make the Bedford Brewery the most successful in the city. To that end, he upgraded the buildings and equipment and went to Europe on a tasting trip to find the recipe for the perfect lager, the most popular kind of beer in America, thanks to German brewers.

He found the perfect blend of malt and hops in the city of Budweis, in Czechoslovakia, so when he came home, he named his beer and his brewery after the town. Brooklyn’s Budweiser Brewery was born. It would take a while for Anheuser-Busch to catch up with him, as the St. Louis brewery had already trademarked the name Budweiser in 1876. But they did. Under threat of a lawsuit, Brown would later have to change the name to the Nassau Brewery.

Brown was a busy man. In addition to his brewery, he was a board member of the People’s Trust Bank, he was doing real estate development deals in several neighborhoods, and for a while he was the police commissioner of Flatbush. He was an ardent Democrat and ran for Congress at one point, too.

His name comes up often in the press during the latter decades of the 19th century as a fierce advocate for Flatbush. He sat on committees that determined the paving of streets, laying down sewers and all kinds of public improvements. He was a “my way or the highway” kind of guy, and made enemies, but he really did love Flatbush. If only everyone could see his wisdom. He must have felt that way when he set about building on Midwood Street in Lefferts Manor.

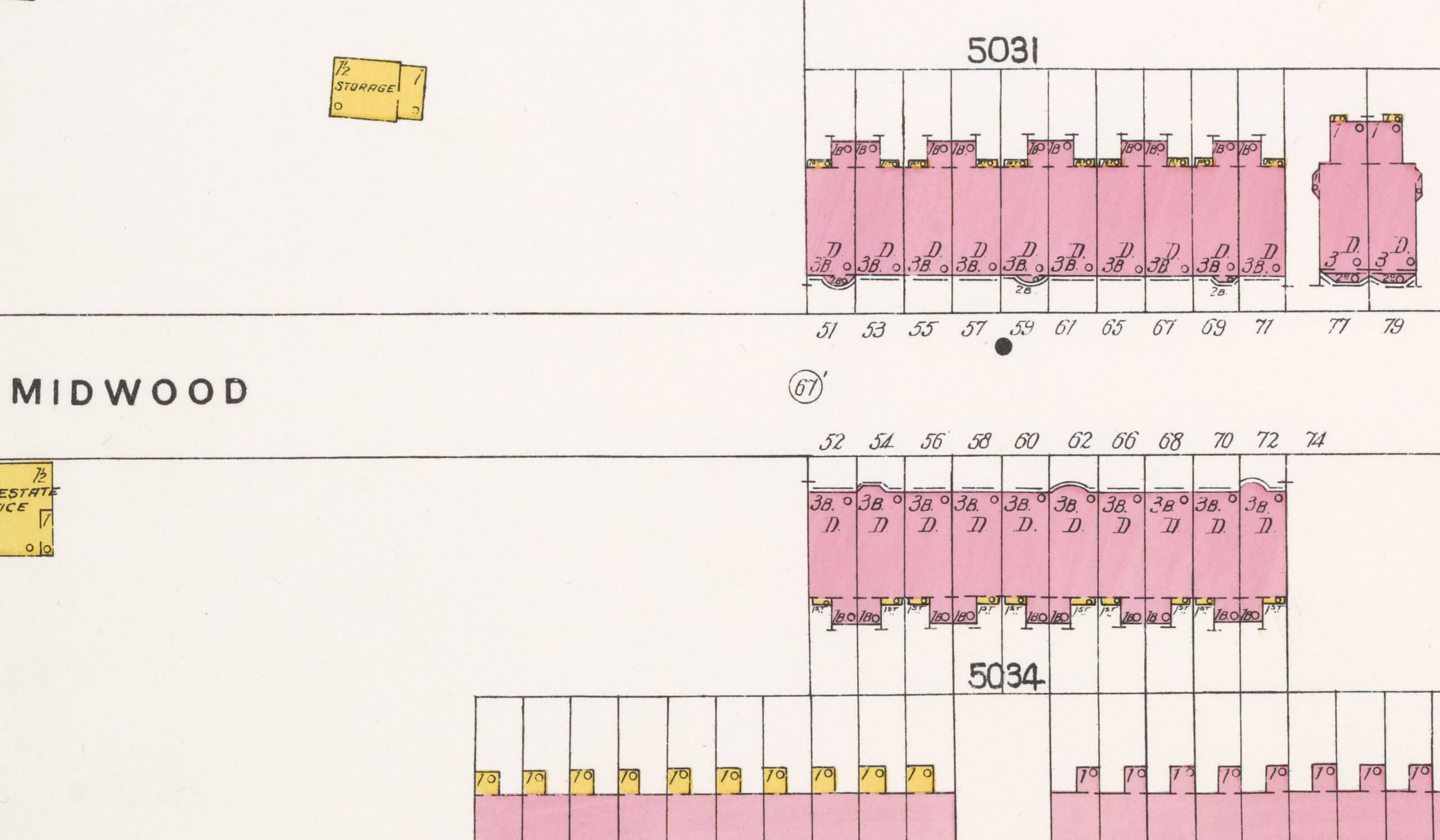

He built other houses in both the Manor and outside of it, but his Midwood houses gave him his start. In 1898 he purchased 20 lots, 10 on either side of the street facing each other on Midwood between Flatbush and Bedford. The houses numbered 51-71 and 52-72, with numbers 63 and 64 omitted from the street numbering.

He hired architect William M. Miller to design the group of houses, all with three stories and a basement, which were among the first row houses to be built within the confines of the Manor. Very little information is available on this talented architect’s life or career. The two rows are identical and represent a transitional period of architecture between the late Romanesque Revival and the new Renaissance Revival style, which was all the rage since the 1893 Chicago World’s Exhibition.

By 1898, most contemporary architects in Brooklyn had abandoned the Romanesque for the new style, but perhaps Miller and Brown counted on a comfortable familiarity in their homes. Not trying to be cutting edge, the style had the look of an older neighborhood like nearby Park Slope, but with just a hint of the new, especially in the interior features and amenities. In fact, Brown’s advertising played on that desire, touting his new homes as more affordable than similar sized houses available in Manhattan and other Brooklyn neighborhoods.

The houses are quite individual but work together as a whole. Miller tosses the architectural kitchen sink into his two groups, with rounded bays, flat facades, angled bays and oriels, arched window and door frames, and a collection of windows and doors of different sizes and configurations.

Miller mixes his stone textures deftly, as well as his choices in brick color and stone trim. His ornamentation includes stained glass, Byzantine leaf carvings, dwarf columns and other decorative architectural elements. Even the pressed metal cornices have different patterns. One of the few elements shared by all is the use of a dogleg stoop, providing an elegant turn as one uses the stoop stairs.

These houses were probably completed in 1899 or early 1900 but didn’t seem to go on the market or sell until the early days of the new century. The block does not appear in the 1900 census. Ads for the houses start appearing in April, showing this row and his smaller houses with two stories and a basement on the next block of Midwood, built at the same time. All were one-families, as per the covenant, but 68 Midwood and its neighbors were more expensive and fancier.

The ads note that the houses featured interior finishes and trims of fine hardwoods, saloon parlors and foyer halls with heavy beamed ceilings, rich enameled faience and hardwood mantels, open nickel plumbing, tile bathrooms, large closets and storerooms, dumbwaiters, electric bells and lighters, chandeliers of beautiful design, the finest hardware, dry cellars and first-class furnaces and ranges. The three-story houses had a two-story extension, allowing for an upstairs dining room.

Brown’s ads also noted the location near Flatbush Avenue and its trolley connections, as well as the fact that “this property is permanently restricted to two- and three-story private residences: no flats, no two-family houses, no stores, no stables. Here you have all city improvements – fine sidewalks and streets, gas, electric lights, water, sewers, etc.”

Brown ended his ads by reminding potential customers of what a great deal they were. The houses were offered for sale at a mere $12,500, much cheaper than a similar house in Manhattan, which would cost $20,000 to $35,000. “CAN YOU BEAT IT ANYWHERE?”

In spite of a long-running series of ads, it took a while for Brown to sell his houses. That was due in great part to the Panic of 1903, which stopped all sales and subsequent building, but the houses would eventually all sell, and Brown would develop more property in the Manor, just outside of its borders and elsewhere in Flatbush. He was truly one of Flatbush’s most prolific and important developers.

The rest of this block of Midwood would eventually be developed with a delightful combination of later architectural styles. Architect Axel Hedman designed a group of white limestone Renaissance Revival houses. He also designed several eclectic Beaux-Arts/Colonial Revival semi-detached homes on the block. Most of the remaining lots feature several different styles of red-brick Colonial Revival homes, all designed by the firm of Slee & Bryson. And finally, outside the borders of the Manor, large 1920s apartment buildings face Flatbush Avenue. This mixture of styles and materials makes this one of Lefferts Manor’s most beautiful and desirable blocks.

68 Midwood Street and John Lefferts Jr.

James Lefferts never moved out of his family’s 18th century homestead, still located on Flatbush Avenue, bordering Lefferts Manor. He oversaw the construction of its blocks and the adherence to his covenant until his death in 1915.

His older brother John Jr., like all of his siblings, was born in the homestead. He attended Erasmus Hall Academy as a boy, moved onto boarding school in New Jersey, and graduated from Rutgers College. He came home to attend Columbia Law School and, after graduating in 1876, passed the bar exam. He went into partnership with Joseph W. Sutphen, creating a successful law practice as Lefferts & Sutphen.

The same year he passed the bar, John also got married. He and his wife, Mary J. Gray, were married at Plymouth Church by the Reverend Henry Ward Beecher himself. They settled down at 616 Carlton Avenue, where the family lived for the next 27 years.

In 1903, John came back to Flatbush. He became the first owner of 68 Midwood Street, buying into his brother’s exclusive development. It must have been a strange feeling to live in a house once part of a field where he played as a child. His arrival no doubt gave some gravitas and “buzz” to the validity of the project.

Like many wealthy businessmen of the day, John was busy with many business and civic activities. He was chairman of the Tunnel Commission for Brooklyn, an advocate for the first East River subway tunnel connecting Brooklyn and Lower Manhattan. He was director of the Flatbush Water Works Company, a charter member of the Montauk Club, one of the organizers of the Flatbush Trust Company, and a member of the St. Nicolas and Holland Societies. He was also a staunch Republican, as were many of Brooklyn’s business elite at that time.

John also dabbled in real estate. He is mentioned in several transfers and sales of property both within and outside of the Manor. Once he moved back to Flatbush, he supported local charities and causes, including those at Grace Reformed Church, which his father and aunt had helped build. He was said to have been known and loved by rich and poor alike.

John Jr. didn’t live at 68 Midwood very long – less than two years, in fact. He died of heart disease on May 28, 1905, at the age of 51. His funeral was here at home, and he is buried in the Lefferts family plot at Green-Wood Cemetery. After his death, his wife, Mary, continued to live here. The couple had no children.

In 1910, Mary married Henry Claus. He was from the well-known Lipsius family of Bushwick brewers and was a member of the Claus-Lipsius Brewery Company. He was a captain in the Cavalry Troop C. Regiment of the National Guard. He was also involved in local Democratic Party politics. This was his second marriage; his wife had died from complications after an operation in 1900, leaving him with a baby daughter.

The address made the papers in 1910, right before the wedding, when David Shaikowitz, 20, was arrested for intently watching the house for hours from the street. There had been several robberies on the block, and neighbors reported him to the police. When he was about to be arraigned, a lawyer showed up and presented papers showing that young Shaikowitz had been employed by an unnamed party to watch the house because Claus was known to frequent the location. He was being sued by that party for breach of promise, and the young man was keeping an eye on him for the plaintiff. The case was dismissed.

By the time he and Mary married, Claus had purchased a large ranch in El Paso, Texas, where the couple would live. The wedding announcement in the Brooklyn papers did not mention his rather déclassé saloon ownership or his other conflicts, which had placed his name in the papers many times, but emphasized his travels in the West, and ownership of the ranch. But Claus seemed to have no pretensions. He listed his occupation as “brewer” in the 1910 census, taken before he and his bride left for Texas.

The same census shows Claus, 44, living here with Mary, 49, and his daughter Hazel, 11, as well as his mother, Catherine Lipsius, 77, and two servants, Kate Clinton, 56, and Mary Walsh, 49.

Three days after their wedding, a quiet family affair, which took place at the Belmont Hotel in Manhattan, the couple were on a Rock Island Railroad train involved in a wreck, which took place in Trenton, Mo. They were on their way to Texas. They were not injured and continued on their trip.

The marriage may not have worked out. Mary Lefferts came back to Brooklyn, and was living at the St. George Hotel, when she died on May 8, 1927. Her death announcement listed her name as “Mary Gray Lefferts,” and only mentioned her as the widow of John Lefferts, Jr. She is buried in Green-Wood and shares a stone with her husband.

The Story Continues

The next family to live in the house was the Bosselman family. Their name first appears at this address in 1913. William Bosselman was a butcher and wholesale meat dealer. He lived here with his wife, Alvina, daughter Gladys and son Rudolph.

When World War 1 broke out, Rudolph enlisted. His grandparents were German immigrants, and many German-Americans were especially keen to prove their allegiance to America. Rudolph was training with the Officer’s Reserve and became a lieutenant in the infantry. He was sent to the front, where he was slightly wounded in the infamous Battle of the Somme in 1918.

The Brooklyn Eagle sent a reporter to the war, who reported that young Rudolph had been wounded and gassed, but not seriously. He was recovering in a field hospital in England. He told the reporter to tell his mother that he was fine, and for her not to worry. He served for 18 months, survived the war, and returned home to 68 Midwood, where he lived for several more years.

The 1920 census shows William F. Bosselman, 52, wife Alvina, 48, and Rudolph, 26. He was employed as a diamond broker. That same year he married Marian Tebo, of 9 Prospect Park West, at the bride’s home. The couple planned to live in Brooklyn. The marriage did not last. Two years later, Rudolph filed for an annulment, charging that his wife had left Brooklyn and was uninterested in their marriage. She initially did not object, but later that year wanted a divorce and alimony. The case was in the papers when the accusations came out, but the result is unknown.

Sometime in the 1920s, the Bosselmans sold the house, and were listed in the 1930 census at an apartment building on Linden Boulevard.

The last owners to appear in the census, which is not public past 1940, are the Blanche family. John Blanche purchased the house for $16,000. He was 72 in 1930, and lived here with his wife, Angelina, 58. Both were born in Italy, and spoke only Italian. Their eldest daughter, Christina, probably ran the household. She was 35, and the proprietor of her own store. It may have been the same store owned by her brother, Joseph, 22, who is listed as a fish man with his own store.

Also in the home was sister Geraldine, 20, who was employed as a comptometer operator. A comptometer was a rather complicated, two-handed adding machine and calculator, a popular piece of office technology at the time. The house was also home to another sister, Louisa, 40, who lived here with her husband, Michael Palladino, 41, a policeman.

The same extended family lived here through to 1940 and beyond. The census that year shows them all here. John and Angelina are 82 and 68, respectively. Christina was now listed as the head of household, and was a partner in a restaurant, perhaps still with brother Joseph, now 32, and listed with the same occupation. Geraldine was now a cigarette machine operator. The Palladinos still lived here as well. Michael, now 50, had retired from the force.

The families who lived at 68 Midwood represent similar changes and demographics in Lefferts Manor over the 20th century. The house first belonged to a wealthy lawyer from a prominent family, then the more upper-middle-class Bosselman family, followed by the middle-class Blanche siblings who, technically speaking, fudged the Manor’s single-family covenant by having the Palladinos pay rent. It was in the census. The only family to do so on that block.

68 Midwood Street has had several more owners since then, all contributing to the ongoing history of this fine house in beautiful Lefferts Manor. Lefferts Manor today is multicultural, filled with homeowners with a strong community spirit, all helping to make this a very special and unique community in the heart of Flatbush, Brooklyn.

[Listing: 68 Midwood Street | Broker: Compass (Paul Murphy)] GMAP

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment