A Deep Dive on WeWork

[Editor’s note: Originally published in The Appraisal on February 15th.]

WeWork is currently trading at $1.55 (at the time of writing), off more than 85% from its peak. Despite the miss, several Wall Street analysts have reaffirmed their bullish outlook on the company — their median price target is $7.75, a 4x+ premium to today’s stock price.

This divergence between investor and analyst sentiment inspired me to take a closer look at the company, including its recent performance, cash position, and tailwinds driving optimism in the flex office space. Overall, it’s an interesting case study in business turnarounds and the growing role technology will play in the management of real estate assets.

1.0 — Neumann, Softbank & Community-Adjusted EBITDA

WeWork’s enigmatic founder and lavish spending habits have been well documented in popular media. WeWork was founded in 2008 and its model — flexible leases of “hip” office space targeting startups in urban areas — became instantly popular. Within 5 years of opening their first co-working space, WeWork had more than 50,000 members across 75 locations worldwide. The company’s founder, Adam Neumann, capitalized on its early success by raising billions in venture capital, most notably from SoftBank’s Vision Fund. In total, the firm has poured more than $17 billion into WeWork, including a $2 billion investment at a $47 billion valuation in early 2019.

Despite the eye-popping valuation, many questions remained around the viability of the co-working business model, particularly the cash burn required to scale and operate locations. These concerns were heightened when WeWork published financial as part of a debt offering that showed massive cash burn (net losses of nearly $1 billion in 2017) along with an unusual new metric — “community adjusted EBITDA” — which deducted not only interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization, but also basic expenses like marketing, general and administrative, and development and design costs in an effort to rationalize its unit-level economics.

These issues, among others, led to Neumann’s ouster in late 2019 ahead of a planned IPO, which was eventually scrapped.

2.0 — Mathrani, Softbank (still) & Free Cash Flow (maybe)

In February 2020, WeWorked brought on new CEO Sandeep Mathrani, a real estate executive who had previously led the turnaround of mall owner General Growth Properties. Mathrani and team were tasked with reducing corporate spending, unwinding non-core investments, and navigating a pandemic which disrupted its core co-working business — not for the faint of heart.

Softbank reaffirmed its commitment WeWork by restructuring the business and issuing more than $5 billion in corporate debt, resulting in 65% ownership of the company. WeWork eventually went public in 2021 via a SPAC merger, which valued the business at about $9 billion.

Since its IPO, the company’s market cap and cash balance have declined to $1.2 billion and $460 million, respectively. In December, the rating agency Fitch downgraded WeWork’s unsecured bonds to CCC, which “represents an extremely high-risk bond or investment” according to the agency.

While the market may be weary of WeWork’s prospects, its management team has remained laser focused on reaching positive EBITDA in 2023 (and not the community version). Mathrani described his approach in an interview last year:

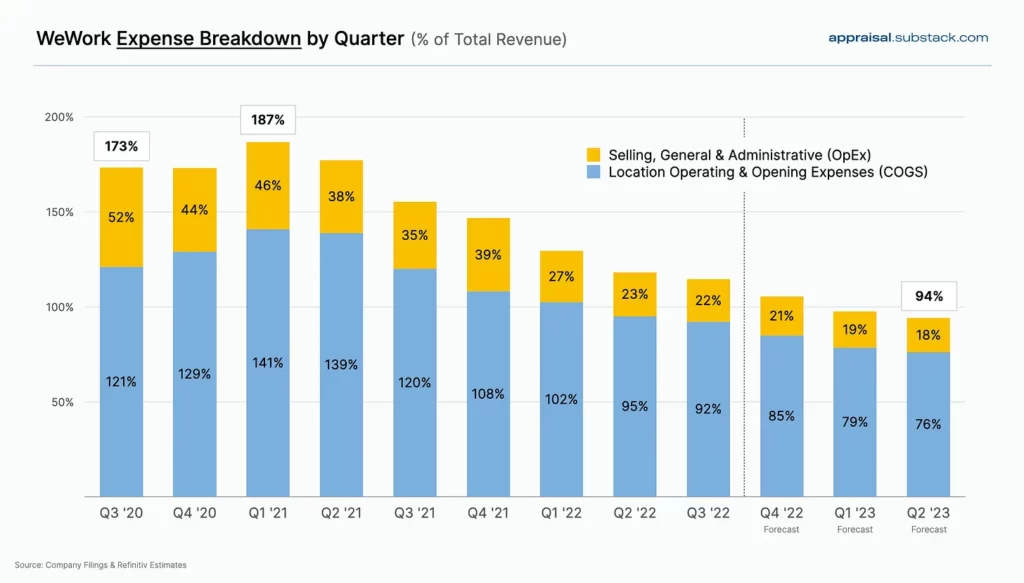

“I knew we could make this company profitable if we could get the SG&A expense structure right and if we could right size the real estate portfolio. So when COVID hit, I put blinders on. I was on a mission to right size the organization from every aspect. […] I’ve cut $1.8 billion of cost out of the system, which means I’ve put the company on a path to profitability.”

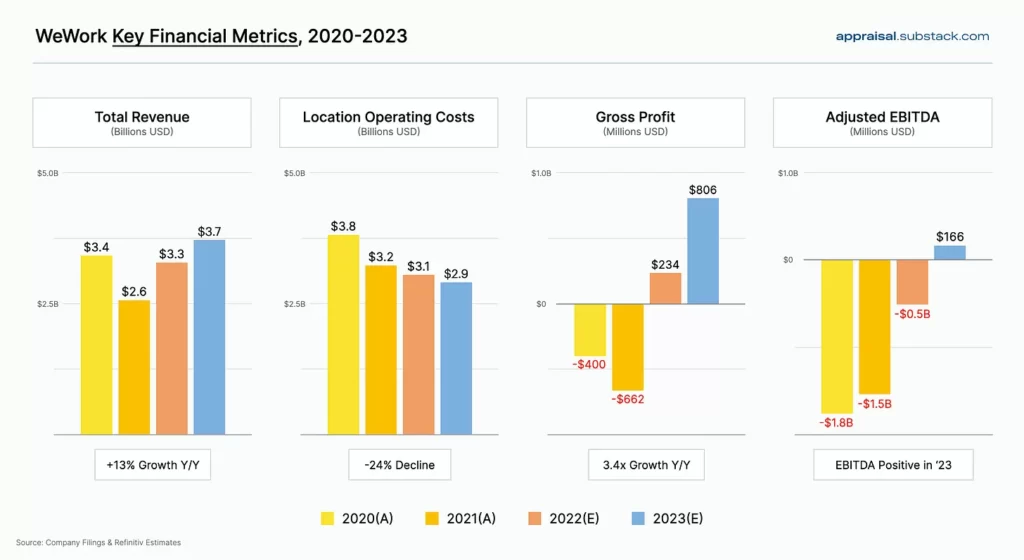

To management’s credit, the underlying business has improved dramatically over the last two years; they’ve both grown revenue and trimmed expenses. The company executed over 240 full lease exits of underperforming locations and 480 lease amendments from the beginning of 2020 through Q3 2022. New leases are typical structured as management agreements (as opposed to master leases), which share revenue with landlords and limit downside risk for WeWork. The company entered 20 new management and revenue share agreements in 2022, representing 18,000 incremental workstations.

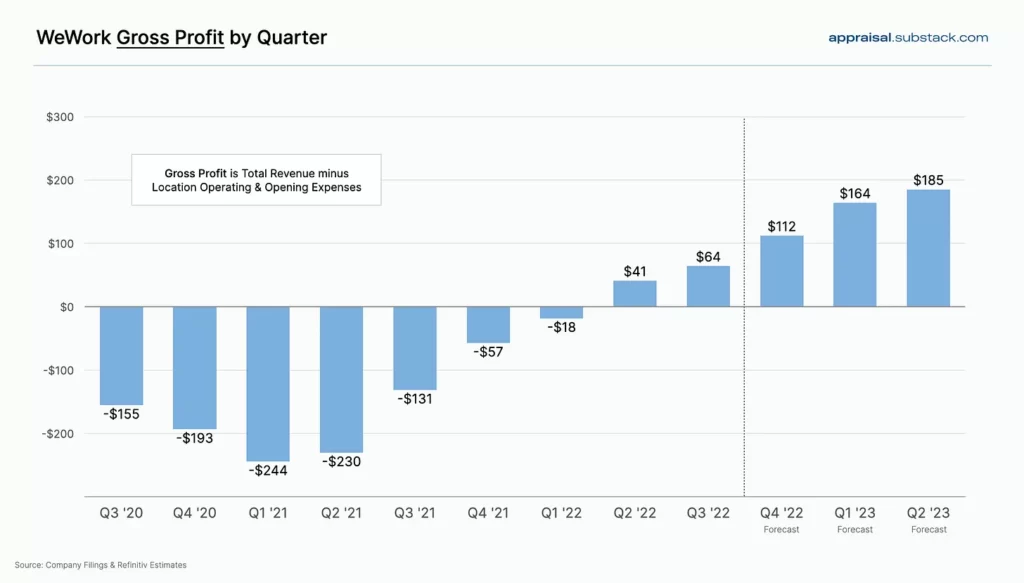

WeWork has also reduced operating costs meaningfully — annualized sales, general & administrative expenses (SG&A) reached $725 million in Q3, down from more than $1.6 billion in 2020. Revenue was $817 million in Q3, up 24% year-over-year, while location operating costs (COGS) declined 3% over the same period. And for the first time since new management took over (and perhaps ever), the company generated positive gross profit in Q2. It’s clear that WeWork of today is much different from WeWork of old.

Looking Ahead — Tailwinds or Tailspins?

Perhaps more importantly, the pandemic’s disruptions to the office sector have created potentially strong tailwinds for WeWork and its peers operating in the co-working / flex office category. A study last year estimated nearly $500 billion of value destruction in the office asset class as a result of COVID-19 and changes in work patterns. Even as the pandemic has ebbed, office occupancy is at only about half of its pre-COVID rate (about 50% occupancy as of January).

This suggests that we may be in the midst of a secular shift in how companies utilize physical space. Many employers may prioritize flexibility as they determine when, where, and how their employees will utilize office space. Some early data to support this:

- 44% of employers plan to increase the amount of flex space in their portfolio over the next two years, according to JLL’s Future of Work Survey. According to CBRE, 51% of respondents reported that in two years they will have a “significant” (10-50%) portion of their portfolios made up of flexible space.

- A recent study startup spending study published by Ramp highlighted an acceleration in spending on co-working space over the last year: “The post-pandemic office is increasingly a co-working space—specifically WeWork. Spending with WeWork increased 90.7% in 2022. It consistently ranked as the second-largest office vendor throughout the year, behind Microsoft Store.”

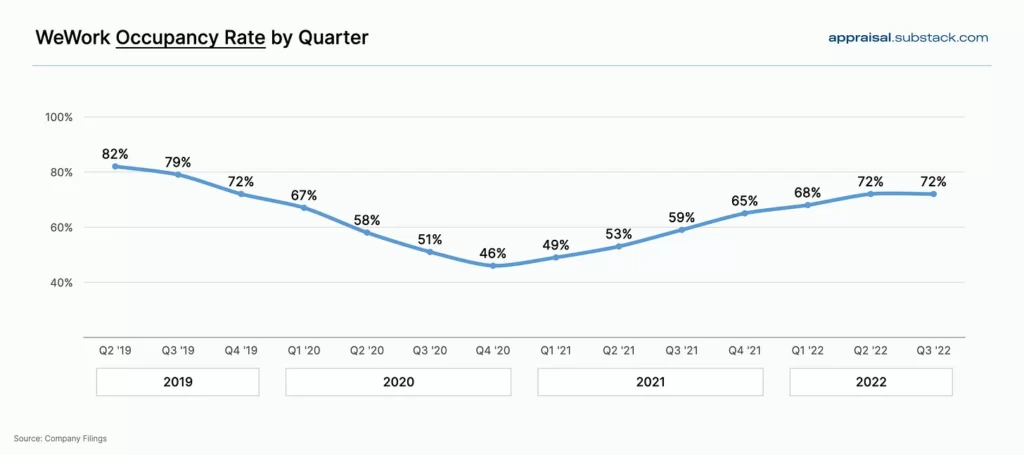

- WeWork’s occupancy rates are outpacing broader office occupancy rates in its core markets. For example, office availability rates in San Francisco reached 28% in 2022 according to Colliers, whereas WeWork’s vacancy rate in SF was 17% as of Q3 2022. It’s clear that companies returning to office environments are increasingly utilizing the flex / co-working model to do so.

WeWork has steadily improved its occupancy rate since its trough in late 2020 — growing from 46% in Q4 2020 to 72% as of Q3 2022. If you believe that a) tailwinds around flex office demand will persist, b) that WeWork will be able to ride these tailwinds to grow occupancy and c) the company can hold costs steady while doing so, there does appear to be a path to generating positive EBITDA over the next several quarters. Back of the envelope math indicates that every 1% increase in occupancy rate leads to about $15 million in additional gross profit per quarter, meaning that if WeWork can grow its occupancy beyond 78%, it should generate gross profit in excess of SG&A expenses.

The big unanswered question for WeWork is if it has enough runway to make it to the other side. The company has taken on meaningful debt, including $3.7 billion of bonds that mature in 2025. To regain control of its destiny, WeWork must begin generating sufficient cash from operations over the next two years to service and/or refinance its debt obligations. Its unsecured bonds are currently trading at less than 50 cents on the dollar — this implies that bond investors have doubts over the company’s ability to refinance its debt during a time when borrowing costs have risen sharply.

Beyond its debt overhang, there are several additional challenges WeWork must navigate on its road to profitability, including:

- Global declines in venture funding to early stage startups, which make up a meaningful percentage of WeWork’s customer base, may impact occupancy rates in 2023.

- Heightened competition from commercial real estate firms and office landlords as they adapt to changing demand for office space. Today only 1.5% of office supply is currently operating as flex space, but several groups have announced new initiatives around flex office. Tishman Speyer, CBRE, Hines and Brookfield have all announced investments or in-house brands in the flex office space. Brad Hargreaves wrote a great overview of the flex office category recently, which is worth a read. WeWork’s counterargument is that its brand recognition and global network of offices give it an inherent advantage over newer entrants to the space.

- Finally, given the company’s stock price and debt overhang, there may be a lack of potential new funding sources to enhance liquidity such as raising new equity. This limits optionality for management.

WeWork’s 2022 Q4 earnings give us a glimpse into the company’s progress towards its key initiatives: growing occupancy, driving down expenses and generating cash flow. There have been no shortage of twists and turns in the WeWork story since its earliest days — it will certainly be interesting to watch how this next chapter plays out!

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.